Over the past two years, 17-year-old Nicky Richens’ life has transformed. He has found independence and a sense of freedom that he has never before known thanks to a small, discrete device called a phrenic nerve stimulator.

Nicky was born with congenital central hypoventilation syndrome (CCHS), a rare disorder that affects the autonomic nervous system and causes kids to essentially forget to breathe. Those that have this condition require 24-hour ventilatory support. The phrenic nerve stimulator, or pacer, can be concealed underneath clothes, provides up to 16 hours/day of breathing support and allows patients to be fully mobile.

“Pacers enable kids to get the health benefits of constant, proper oxygenation and ventilation without looking different or being restricted by it, which is huge in the life of a child,” said Maida Chen, MD, director of Seattle Children’s Hospital’s Pediatric Sleep Disorders Center. “With pacers, kids go on to have very meaningful lives because they are healthier, they feel better and they are free to participate in their life.”

Nicky was three days old when he became tethered to a ventilator, which weighed about 20 pounds, had tubing that attached to a tracheotomy in his neck, was noisy and required the company of a nurse at all times once he started school. Needless to say, this greatly impacted his ability to live a normal life.

“Nicky couldn’t participate in daily life like the other kids,” said his mom, Joy Lund. “He couldn’t get up to sharpen a pencil, go out for recess or attend gym class, and it was very hard to socialize. Now Nicky’s quality of life of has dramatically improved – it’s like night and day.”

Phrenic nerve stimulator offers Nicky new found freedom

Nicky’s journey to freedom began two years ago, when his family learned that Seattle Children’s was (and still is) the only hospital in the region offering phrenic nerve stimulators for children. They came from their hometown of Chehalis, Wash., to see Chen.

“We decided very quickly that this device was right for Nicky,” said Lund. “He always had low energy and was not able to make it through a full day of school. He would have to come off the ventilator to do simple things like use the restroom or go to the grocery store. And he was in the hospital almost every winter for pneumonia. It was not a good quality of life.”

During the surgery he had two years ago, neurosurgeons clipped electrodes on the phrenic nerve, which is the main nerve that stimulates the diaphragm and enables breathing. The implantation takes about two hours and the recovery can be less than a week. The pacer can be used once the area heals, usually after about six weeks. The pacer is then activated by an external radio transmitter that’s about the size of two decks of cards – a major difference from a 20-pound ventilator.

Nicky’s recovery went very well and the result has been remarkable.

Nicky’s recovery went very well and the result has been remarkable.

“I’m so glad we got the pacer because it’s had a tremendous impact,” said Lund. “He is very happy, healthy and has much more stamina. He can make it through a full day of school, he hasn’t been hospitalized since he got the pacers and he can even play sports. Now, whatever he grows up to do, the pacers will allow him to reach his full potential.”

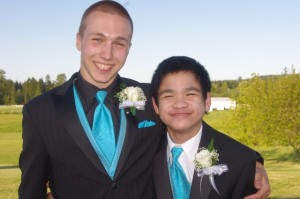

Chen is also very pleased with the result, and was happy to hear that Nicky was even able to attend prom.

“It has revolutionized his life. He is much more awake and functional because he is maintaining consistent and safe levels of oxygen and carbon dioxide,” said Chen. “His body no longer needs to focus on breathing and can now allow him to just focus on being a teenager.”

Kids with other conditions may be candidates for the device

Chen said pacers can also be a great option for kids who have other forms of milder central hypoventilation, including those who just need ventilation when they are sleeping. For those reasons, pacers may be a good option to consider for kids who have had damage to their respiratory control centers from brain tumors or a traumatic brain injury.

“The phrenic nerve stimulator can help a variety of patients who require respiratory support by providing stability in their overall health and allowing them to maximize their neurodevelopmental ability,” Chen said. “I’ve seen patients’ lives take a huge upswing because it’s as though they’ve woken up for the first time.”

If you’re considering a phrenic nerve stimulator as an option for your child, please contact Seattle Children’s Neurosurgery Program at 206-987-2544.