The day doctors told Karen Twede her son Erik had Duchenne muscular dystrophy, she went straight home and searched for the mysterious illness in her medical dictionary. She read: “A progressive muscle disease in which there is gradual weakening and wasting of the muscles. There is no cure.”

“My breath caught in my throat,” Twede said. “It was a terrifying reality to accept.”

Thankfully, several clinical research studies being offered at Seattle Children’s Research Institute are giving hope to parents facing the same devastating diagnosis.

The studies, led by Dr. Susan Apkon, director, Seattle Children’s Department of Rehabilitation Medicine and an investigator in the research institute’s Center for Clinical and Translational Research, offer promise to better treat, or even cure, Duchenne, through the use of new therapies with fewer side effects.

“When I meet with patients with Duchenne and their families today, we have a very different conversation than we might have had 10 years ago,” Apkon said. “Today I ask my patients ‘What do you want to be when you grow up?’ because I believe in their future. I’ve been able to look ahead and see the research being done nationally and internationally and there seem to be treatments on the horizon.”

What is Duchenne muscular dystrophy?

Duchenne muscular dystrophy is the most common fatal genetic disorder diagnosed in childhood, affecting approximately one in every 3,500 live male births. The disease primarily affects boys; however, it occurs across all races and cultures.

Patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy are unable to produce dystrophin, allowing their muscle cells to be damaged easily. The progressive muscle weakness leads to serious medical problems, particularly in the heart and lungs. Young men with Duchenne typically live only into their late twenties.

Duchenne can be passed from mother to child, but approximately 35 percent of cases occur because of a random spontaneous mutation.

Erik’s story

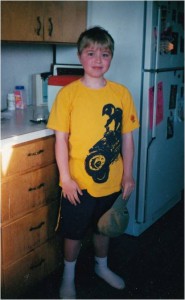

Erik, 22, was diagnosed with Duchenne at age 3, though Twede said her son did not begin showing signs of muscular degeneration until he was 9 years old. By the time Erik was 15, he could no longer walk.

Today, Erik is a senior at Western Washington University. While he takes pride in his ability to navigate campus independently, he lives with his parents and depends on them for help with basic tasks like getting ready in the morning and preparing meals.

“The guys with Duchenne grow up wanting more independence, just like any other adolescent, but their body forces them to depend on others,” his mom said. “This disease is constraining. While other college students watch their world get bigger, his is getting smaller.”

After Erik was diagnosed, Twede spent years gathering information on her son’s condition. She searched libraries, the internet and attended annual Duchenne conferences around the country. Some of the things she learned were helpful, others were frightening.

“When Erik was 5 years old I attended a conference with a surgeon who showed pictures of untreated young men with Duchenne,” Twede said. “Their bodies looked like pretzels. I remember sitting on the bathroom floor in a cold sweat afterwards, trying not to pass out.”

But as the years passed, Twede began hearing about promising new treatment options. Clinical research studies around the country were testing new therapies that could change the progression of Duchenne. Unfortunately, the studies weren’t available locally. Pediatric patients in the Pacific Northwest had to travel to other parts of the country to participate.

For Twede, that was not acceptable. At a conference in 2009, she met Apkon, and told her that patients like her son deserved access to the latest research. Apkon agreed, and made it her mission to bring clinical drug studies to Seattle Children’s Hospital patients that could better treat, or even cure, Duchenne.

“There was a sense of urgency when I arrived in Seattle,” Apkon said. “Passionate parents were not willing to wait another day for therapies to treat their sons – and I believed they shouldn’t have to.”

Bringing hope to the Pacific Northwest

Today, there are several clinical research studies at Seattle Children’s open to patients with Duchenne. Those who have a specific genetic mutation can participate in a study with Ataluren, a medication designed to repair a gene that is typically misinterpreted by proteins in the body so that patients can begin producing dystrophin, preventing further muscular degeneration. So far, Apkon said the medication is showing promise in helping patients maintain their ability to walk.

Two other studies Apkon brought to Seattle Children’s have been designed to help boys with Duchenne who are missing part of a gene with a therapy called exon skipping which reconnects the genetic sequence by “skipping over” the missing piece.

A fourth study Apkon has enrolled patients in is with the medication Tadalafil – better known as Cialis. Tadalafil improves blood flow and researchers believe it could help with muscle recovery in patients with Duchenne.

In response to Seattle Children’s unique clinical and research approach, Seattle Children’s was recently named a Certified Duchenne Care Center by Parent Project Muscular Dystrophy, the leading advocacy organization working to end Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Seattle Children’s is just the fourth center to be certified by PPMD, recognizing the hospital’s dedication to improving care for people living with Duchenne.

“These therapies have tremendous potential that is changing the long-term outlook for patients,” Apkon said. “That’s why I’m focusing on making sure my patients stay healthy through comprehensive muscular dystrophy clinics. They can see amazing group of dedicated providers from many specialties including nursing, neurology, cardiology, pulmonology, endocrinology, physical and occupational therapy, nutrition, and social work all in one visit and receive a comprehensive set of recommendations.”

Change for the next generation

Erik lost the ability to walk at age 15, which unfortunately currently excludes him from participating in most therapeutic clinical research studies. Still, he has participated in several survey studies in hopes of helping scientists learn more about his disease.

“Care for this disease has changed significantly during my son’s life,” Twede said. “Dr. Apkon has brought hope to the families at Seattle Children’s. I believe this might be the first generation of boys who don’t die from Duchenne.”

In her career, Apkon said she has seen dramatic change in the prognosis of patients with Duchenne and is optimistic about the future.

“When I first started taking care of patients with Duchenne there were boys, but there weren’t any young men,” Apkon said. “They didn’t survive past their teens. I now treat young men who are going to college, grad school and even law school! Some are getting jobs and starting families. They still have significant medical issues and functional limitations, but they are surviving. Clinical research will offer even more hope for the future.”

To learn more about the most current research on muscular dystrophy, contact the local chapter of the Muscular Dystrophy Association or talk to your doctor about clinical trials on muscular dystrophy.

Resources:

- Seattle Children’s: The Meaning of Muscular Dystrophy

- Seattle Children’s Rehabilitative Medicine

- Parent Project Muscular Dystrophy

- Muscular Dystrophy Association

- Seattle Children’s Research Institute’s Center for Clinical and Translational Research