In 2014, the Seattle Children’s Research Institute will implement life-saving projects, begin new studies to keep children safe and continue searching for ways to prevent and cure diseases that threaten some of our youngest patients. We are celebrating the New Year by highlighting some of the work that has researchers excited about 2014.

Cleft lip is one of the most common facial malformations in the world, affecting one in 700 children. Still, few researchers focus on this condition. But craniofacial scientist Timothy Cox, PhD, is leading efforts at Seattle Children’s Research Institute to determine how cleft lip might be prevented in the future.

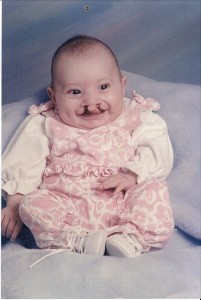

A cleft lip, which can also present with cleft palate, occurs when a baby’s lip and mouth do not form properly. Children with these conditions can have difficulties eating, drinking and talking. They may also have significant dental problems and suffer frequent ear infections and hearing loss.

Despite these serious effects, few researchers study the causes of cleft lip because it occurs so early in pregnancy – around the fifth or sixth week.

Jessica Schend, a 17-year-old girl from Lake Stevens, was born with cleft lip and palate. She has been treated at Seattle Children’s Hospital’s Craniofacial Center since birth and has had 18 surgeries so far.

While she was growing up, people often made fun of the way Schend looked.

“I used to think I was ugly because people were so rude to me,” Schend said. “It hurt my feelings and made me feel like an outsider.”

Cox is trying to help families like Schend’s by searching for ways to prevent cleft lip so fewer children have to face these challenges.

“Most people recognize cleft lip and palate but they don’t appreciate the impact and long term treatment needed,” Cox said. “There’s so much that can be done to improve things.”

Genes may hold clues to preventing cleft lip

The Cox Lab is using chicken and mouse embryos to determine how specific genes influence facial development and how they might be manipulated by simple dietary interventions to decrease the severity of a cleft lip or prevent the condition entirely.

“These animals have the same genes as humans and their faces are put together in the same way so they can also get cleft lip,” Cox said. “We can turn on and off genes and see how it impacts their face. We can understand what cellular processes disrupt lip formation and how nutritional factors can change the face shape.”

To observe the development of a cleft lip, Cox uses high resolution 3D-imaging – a technology that is available in few labs worldwide.

“We are in a unique position to quantify how genetic mutations change the facial shape and give rise to this disease,” Cox said. “Few groups in the world are attacking this problem in the manner and detail that we’re doing it.”

Cox hopes to eventually identify a panel of genes that parents can be screened for to determine their risk of having a child with cleft lip. For those at risk, researchers may also be able to identify vitamins or other nutrients that may minimize or prevent the condition entirely.

“Instead of relying on post-surgical repair we may be able to prevent this condition all together,” Cox said. “We believe nutrition is crucial before getting pregnant and stress may activate the same gene pathways through hormones that can have positive and negative effects on facial development.”

Seattle Children’s Craniofacial Center is one of the largest in the country, consisting of over 50 healthcare providers from 19 specialty areas, dedicated to providing all aspects of care to children with craniofacial conditions.

Resources:

- Seattle Children’s Research Institute

- Seattle Children’s Craniofacial Center

- The Cox Lab

- Cleft Lip and Palate background information

If you’d like to arrange an interview with Dr. Timothy Cox or Jessica’s family, please contact Seattle Children’s PR team at 206-987-4500 or [email protected].