Children with type 1 diabetes and their families have to do several calculations throughout the day to stay healthy. Did my daughter check her blood sugar before breakfast? Does she need an extra snack because she has gym class? Is there someone at school to help my child check her blood sugar?

Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disease that injures the insulin-producing cells in the pancreas and leads to a lifelong requirement of daily insulin injections. It is a considerable burden of care on patients and parents, who effectively never get a rest from the demands of staying healthy and safe.

According to the American Diabetes Association, about 1.25 million Americans have type 1 diabetes. A new $1 million grant from The Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust will get doctors and scientists at Seattle Children’s Research Institute one step closer to better treatment for type 1 diabetes by studying the use of immunotherapy to treat the condition. The work is in collaboration with researchers at Benaroya Research Institute at Virginia Mason (BRI).

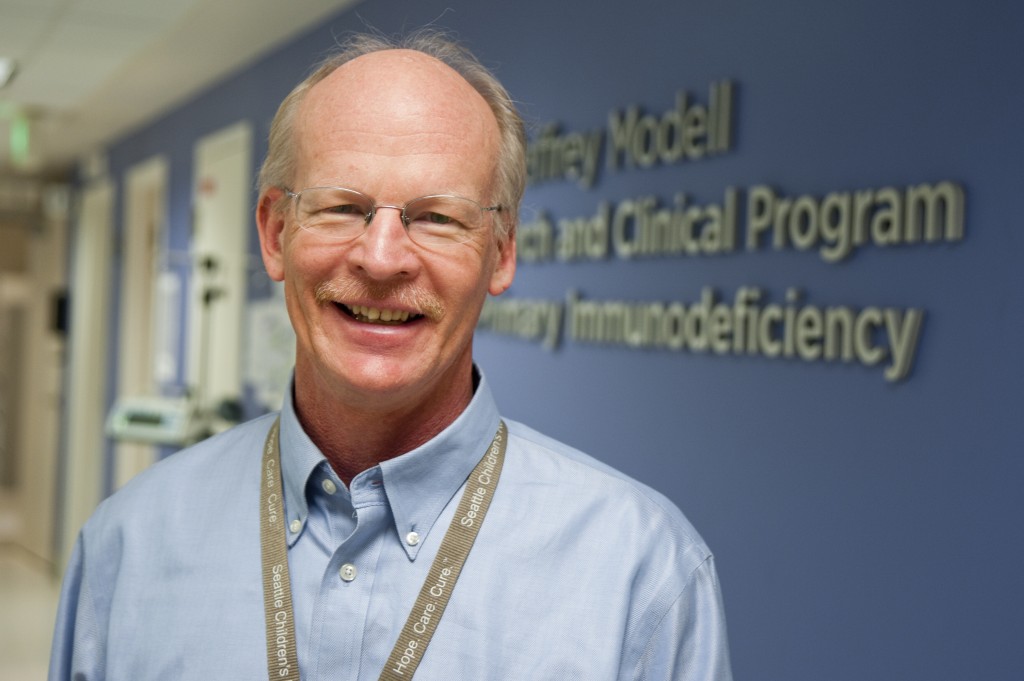

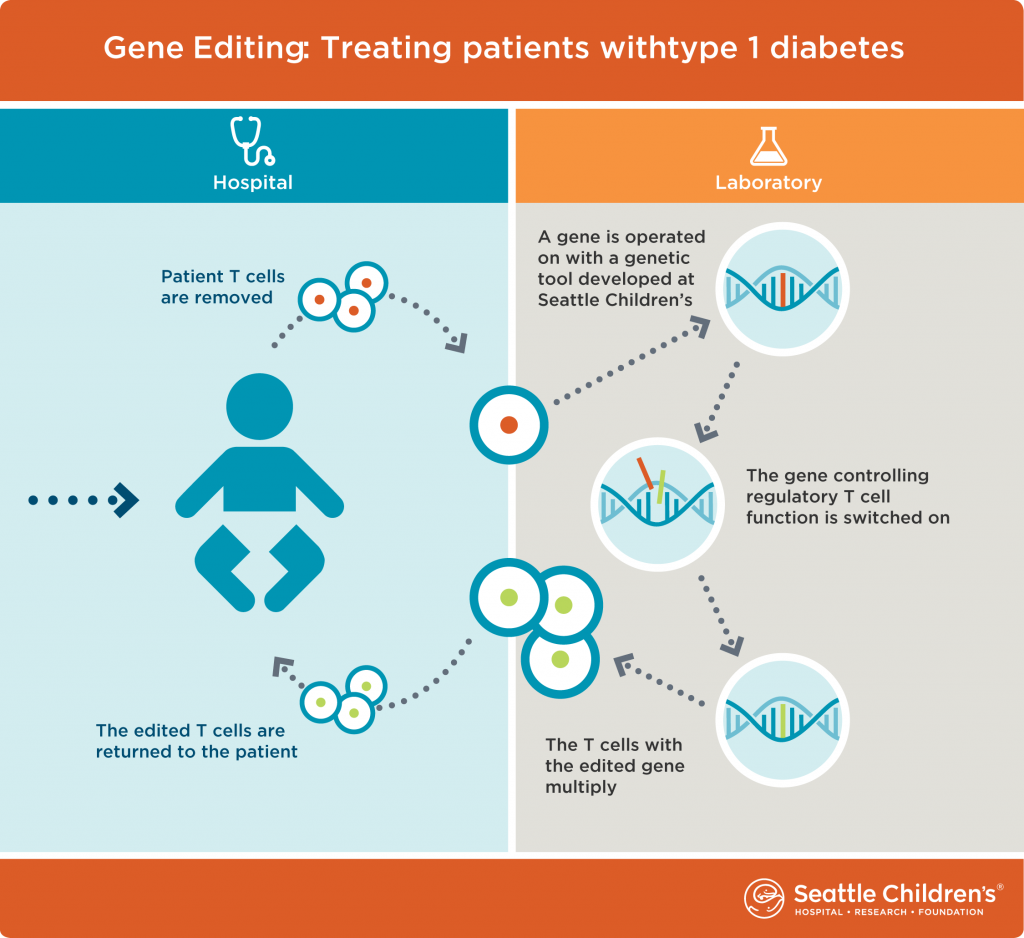

“The only treatment for type 1 diabetes is to give insulin to patients because their bodies cannot produce it,” said Dr. David Rawlings, Director of the Center for Immunity and Immunotherapies at Seattle Children’s Research Institute and Chief of the Division of Immunology at Seattle Children’s Hospital. “With immunotherapy, our goal is to take a patient’s own T cells, modify them, and then send the cells back into the patient where they will help protect insulin-producing cells from injury. That advancement would free people with type 1 diabetes from having to take insulin to manage blood sugar and improve their quality of life.”

Juliana’s diagnosis of type 1 diabetes

Juliana Graceffo, an 11-year-old with type 1 diabetes, loves to dance—you can find her at home spinning, turning and kicking her way around the house. Juliana’s health depends on remembering to test her blood sugar throughout the day and taking carefully calculated doses of insulin.

“I wake up at 6:00 in the morning to test my blood sugar before I leave to catch the bus,” she said. “I prick my pinky, ring or middle fingers on the left hand to get a drop of blood. I have to test my blood sugar before lunch, when I get home from school and before meals or snacks.”

Juliana was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes when she was 4 years old. On Christmas Eve of 2008, Juliana became lethargic and sick. On Christmas Day, she woke up delirious with breathing difficulties. An ambulance brought Juliana to Seattle Children’s. Her blood sugar was extremely high, and she had developed diabetic ketoacidosis, a dangerous complication of type 1 diabetes. Juliana sees Dr. Craig Taplin at Seattle Children’s Hospital to manage her diabetes.

“It was a life-changing trauma and diagnosis,” said Juliana’s dad, Greg Graceffo. “We stayed at the hospital for a week until she recovered. We had to learn about counting carbs and how to give insulin shots and test blood sugar. We needed to learn about materials like syringes, lancets and test strips.”

Now that she’s in middle school, Juliana has taken on more responsibility in managing her diabetes.

“Her mom, Elisa, and I are proud of her strength, poise and maturity in how she deals with diabetes,” Graceffo said. “She has a lot of daily challenges she has to deal with, and day-to-day she is still positive and happy.”

The science behind potential new therapies

Type 1 diabetes affects how the body uses glucose, the sugar that fuels the body’s cells. Normally, the glucose level in the blood rises quickly after a meal and triggers the pancreas to make the hormone insulin, which delivers glucose to the body’s cells.

But in people with diabetes, the body either cannot make or cannot respond to insulin properly. A type 1 diabetic’s immune system attacks and destroys the cells in the pancreas that produce insulin. Without insulin, glucose cannot get into the body’s cells and it stays in the bloodstream, leading to a higher than normal blood sugar level that can result in immediate and chronic health problems.

“Researchers know that many people with type 1 diabetes have a genetic predisposition for the condition,” Taplin said. “In the context of that predisposition, at some point those people are exposed to one or more external triggers that results in the loss of insulin-producing cells and the development of diabetes. Researchers are still working to understand what those triggers are, but it remains unclear.”

Researchers do know that the genetic predisposition is related to genes that control immune function, especially important immune cells called T cells.

“In type 1 diabetes, a type of immune system cell, called an effector T cell, malfunctions and attacks pancreas cells that create insulin,” Rawlings said. “Normally, effector T cells attack foreign viruses, not the body’s own cells. With this research, we will edit genes in these cells and change these ‘dangerous’ cells into regulatory T cells, another type of immune cell that regulates an immune system’s response and keeps it from going into overdrive. We expect these gene-edited

regulatory T cells, when returned to a diabetic’s body, will stop effector T cells from destroying the body’s insulin-producing cells.”

Rawlings is partnering with Dr. Jane Buckner, President of Benaroya Research Institute. Buckner and her team have developed methods to pinpoint exactly which problematic T cells to target for editing. Once they have identified the T cells for this research, they will work with Rawlings and his team for the gene editing work and develop methods to efficiently manufacture regulatory T cells for immunotherapy clinical trials.

“This important collaboration with Seattle Children’s researchers allows us to combine our expertise to attack this complex problem,” Buckner said. “Our hope is that this research could lead to fundamentally new ways to prevent loss of immune system regulation, a common problem in autoimmune diseases like type 1 diabetes.”

Juliana’s hope for a cure

For Juliana and her family, managing type 1 diabetes is an hour-by-hour way of life that has become routine. They raise money for diabetes research and participate in the Nordstrom Beat the Bridge to Beat Diabetes Walk benefitting JDRF. When Juliana and Graceffo pause to think about what a cure would mean for them, it brings tears to their eyes.

“It’s hard dealing with type 1 diabetes every day,” Juliana said. “A cure would mean that I don’t have to think about diabetes all the time, and I can just be normal.”

Her family hopes that in Juliana’s lifetime, treatments will improve and researchers will find a cure.

“I hope people doing research know we support them and are advocating for advancements,” Graceffo said. “A cure would have a tremendous impact on Juliana’s life and the lives of many others like her. We are optimistic about the future and excited about what is possible with the new technologies and research we’ve been learning about.”

Resources

- Seattle Children’s Diabetes

- Seattle Children’s Research Institute, Center for Immunity and Immunotherapies

- Benaroya Research Institute at Virginia Mason (BRI)