As the 2013 to 2015 state budget moves toward approval this year, immunology researchers and clinicians at Seattle Children’s will be following it as closely as many of us followed last Sunday’s Super Bowl.

They will be cheering for one small line item deep inside the document: A provision to ensure every baby born in Washington is screened at birth for severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), a rare condition that makes it impossible to fight off infection.

Children’s physicians have been quietly working with the Washington Department of Health (DOH) Newborn Screening Program for years to bring the screening test to families in Washington state. The federal government recommended in 2010 all states add SCID to newborn screening tests.

Infections without end

For babies with SCID (also known as “bubble boy” disease), common infections of early childhood – like ear infections – can become chronic, complicated and life-threatening.

That’s what happened to Hayden Boone of Anchorage, Alaska.

“At first, we thought he was just one of those babies who would need tubes for chronic ear infections,” said his mom, Jacquie Boone-Filley. “Then he got thrush from the antibiotics, and that didn’t clear up, either.”

When he was seven months old, Hayden became critically ill with a type of fungal pneumonia – an illness that is usually seen in patients with suppressed immune systems. Hayden’s pediatrician in Alaska reached out to Children’s to help figure out what was wrong.

Hayden was diagnosed with SCID, and promptly came to Children’s for treatment. The first step for Hayden was to shake the pneumonia; if he survived, he would need a stem cell transplant.

With a stem cell transplant, people with SCID can lead normal lives. But if it’s undetected and untreated, SCID typically leads to death before a baby’s first birthday.

Screening saves lives

Alaska, like Washington, is on the cusp of adopting SCID screening. It can’t come too soon, said Boone-Filley.

“If Hayden had been screened for SCID as a newborn, we wouldn’t have had to go through that scary spell of pneumonia,” said Boone-Filley. “He would have had a stem cell transplant before he got so sick, and we might have spent three or four months in Seattle for treatment instead of seven.”

Starting treatment before a life-threatening infection takes hold can prevent long-term consequences and save lives, said Suzanne Skoda-Smith, MD, an immunologist.

Without newborn screening, she said “the first serious infection is often the first hint that something is terribly wrong – and by then, it’s too late for early intervention.”

Screening is a bargain

In Washington, the SCID screen will add about $8 per baby to the state’s newborn screening fee, which is typically reimbursed by insurance or Medicaid. Since about half the newborns in the state are covered by Medicaid and the state picks up half the screening tab for each of them (the federal government pays the other half), that $8 per baby adds up to $170,000 a year for Washington taxpayers.

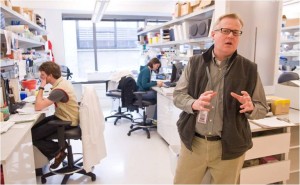

That’s a bargain, said Troy Torgerson, MD, PhD, an immunologist and director of the Immunology Diagnostic Laboratory (IDL) in the Center for Immunity and Immunotherapy at Seattle Children’s Research Institute.

“If it’s not caught early, the medical care for one baby with SCID can run into the millions of dollars,” said Torgerson. The DOH expects the screening to detect one to two babies with SCID in Washington each year.

Every dollar the state spends on screening is expected to generate more than $4 of benefit for taxpayers, according to a DOH analysis.

Finish line in sight

Mike Glass, director of the state’s newborn screening program, often works with clinical divisions at Children’s because the conditions the lab screens for are treated here.

But, he said the collaboration with the immunology group was different. His team needed guidance and training in a very specific area laboratory expertise.

“The type of DNA analysis required for the SCID screening is brand-new for the state lab,” explained Torgerson. “But it’s something we do in my lab all the time.”

He and the IDL team rolled out the red carpet for the DOH team – sharing testing protocols and helping the team gain the experience needed to do the screening. The team from the state laboratory also visited states that have already implemented universal screening for SCID.

Now, everything is in place for SCID screening to start in Washington. Everything, that is, except the funding.

After watching the 2011 to 2013 budget cycle sail by with no SCID screening, everyone involved was overjoyed in December to learn that outgoing Gov. Christine Gregoire had included it in her final budget. They’re cautiously optimistic that now Gov. Jay Inslee, will leave it intact and that it will survive the biennial budget battle.

Full circle: Diagnosis, treatment, research

While the SCID screening process moves forward, so, too, do clinical care and research at Children’s.

Babies diagnosed with SCID will be referred to Children’s, where the IDL can provide a precise genetic diagnosis to help the clinical team plan the best course of treatment for each child.

The IDL and Children’s Department of Laboratory Medicine are developing a one-stop screening panel for all known immunodeficiency genes – including the 20 or so genetic defects that cause SCID and a few hundred more that result in other immunological problems.

Since the technique the state lab will use to detect SCID will also identify babies who have many of these other immune system problems, noted Torgerson, “this could potentially have an impact beyond identifying babies with SCID.”

Children’s is also working on promising new treatments. Last year, the National Institutes of Health awarded $12 million to a multi-center research team, including David Rawlings, MD, at the Research Institute’s Center for Immunity and Immunotherapies, to work on a potential new gene replacement therapy to treat SCID.

That is great news for kids like Hayden, who returned to Alaska in January after seven months of treatment at Children’s and a successful stem cell transplant.

“He doesn’t have SCID anymore,” said Boone-Filley. “He’s a whole new kid.”

For Boone-Filley, the personal is also professional. She’s a laboratory technician at a community health center in Anchorage that conducts newborn screening tests.

“I never in the world thought I’d be advocating to add something to the screening panel,” she said. “But then again, I never imagined that my baby could be born with SCID.”