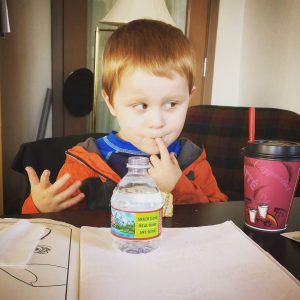

From his appearance alone, 3-year-old Hamilton McNamee looks like a typical kid. He is rambunctious and playful with strawberry blonde hair and a mischievous smile.

As he climbs on the tables and chairs in Starbucks at Seattle Children’s Hospital, his mother Claire casually states, “He’s going to wander around a little. It’s fine.”

What’s different about Hammie, as his family affectionately refers to him, is that he has a condition known as tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC), a rare genetic disease that causes tumors to grow in various parts of the body, including the brain and other vital organs. Though the tumors are benign (which means they aren’t cancerous), they impact a child’s development in a variety of ways depending on where they grow and how big they get.

At age 2, Hammie experienced some seizure-like behavior after a bout with hand, foot and mouth disease. His primary care provider referred Hammie to Seattle Children’s First Seizure Clinic where tests revealed that he had growths in his brain and he was diagnosed with TSC.

Learning about an unfamiliar diagnosis

TSC is rare and no cure is currently available. The Tuberous Sclerosis Alliance states that there are about 50,000 people in the United States with TSC. The disease is genetic and affects people to different degrees. Hammie’s case is considered mild. He is somewhat developmentally delayed in his speech though his vocabulary is growing. He is mainly non-verbal as he approaches his fourth birthday, but in many ways, he’s just a typical young boy.

“I call him my monkey child because he’s always running, jumping, climbing and swinging,” McNamee said.

What’s difficult for McNamee is Hammie’s inability to express himself verbally.

“I can see how badly Hammie wants to make friends and how much he wishes they’d understand him. It breaks my heart, but he never seems sad about that little bump in the road,” said McNamee. “I ask other parents how they would feel if their child could not say ‘I love you mommy or I love you daddy.’ It’s flat-out heartbreaking sometimes.”

Hammie also experiences epileptic seizures. Over the past year, the family has worked with Seattle Children’s physicians, including neurologist Dr. Stephanie Randle, to try and find the right combination of medications to control such episodes, but the family is constantly in fear of “the big one” that may leave him trapped in his own body and unable to communicate.

“As a neurologist, I’m interested in TSC because most of the patients have seizures that affect their development. That’s an area where we can provide the right care and medication to help,” said Randle.

“TSC is a multi-system disorder, so it can affect a lot of areas including the brain, eyes and kidneys,” said Randle. “Right now, there is no cure, but there is treatment specific to the individual. Early intervention is also helpful.”

Hammie is also a sensory-sensitive child and has problems sitting still and focusing. He attends a half-day developmental preschool at Totem Falls Elementary in Snohomish, Washington, where he receives speech, occupational and behavioral therapy in a classroom setting. The therapy is helping, but not fully eliminating, his frustration of being unable to communicate verbally.

The path toward coping with TSC

So how does one deal with such a condition? Organization and routines are critical for the McNamee’s who also have a 13-year-old daughter and a 2-year-old son with celiac disease.

“The logistics of caring for a TSC kiddo are exhausting most days. I have 25 Google calendars to coordinate my family,” McNamee said. “We have a calendar just for doctors, specialists and therapy appointments. Our mornings start with medication and our goodnights are punctuated by the same. Keeping the same routine every day is helpful.”

There is no predictable prognosis for individuals with TSC and the uncertainty can create a considerable amount of stress for families. Fortunately, Seattle Children’s has been able to help the McNamees.

“The staff has been amazing,” McNamee said. “Just knowing that they’ve taken care of kids thousands of times before makes me feel so much safer than if I took him to a hospital not made for children. And thank goodness for the financial assistance they offer as well. Treating brain tumors is not an inexpensive venture and I am so grateful for all the donors who give so much money to ease the burden on families like ours.”

Randle said that providing this type of specialized care and support is often key for kids with TSC.

“The earlier we can get to these kids and start handling their symptoms while providing social and financial support, the better off kids like Hammie will be,” said Randle. “And with the right coordinated care, many can have more typical development.”

With the help of his care team at Seattle Children’s, Hammie continues to develop and reach new milestones.

McNamee’s mother is a true optimist about Hammie’s improvement and the family is excited to take a camping trip when the school year concludes.

“He is just the most excitable, happiest, climbing-est little monkey in the neighborhood,” said McNamee. “We don’t let TSC or seizures hold us back!”

Resources

Laser ablation for tumors

Neurology