In recognition of Childhood Cancer Awareness Month, Louisa Cranston shares her experience caring for her 3-year-old son, Henry, who was recently diagnosed with cancer.

My husband Robert and I are both Seattle natives. We met and began dating 10 years ago now, and will have been married for five years this October. Our son Henry was born in 2015, and his sister Alice followed in 2017.

Henry was and in most ways still is a very typical toddler. He loves playing outside, watching cartoons, and spending quality time with his people. He is an eager helper in the kitchen and anything he can do by himself, he wants to do by himself. Often when we are together, he echoes the words of his hero Daniel Tiger: “Mommy, I like to be with my family!”

When Henry arrived in our lives and made me a mother, I experienced a whole new set of emotions for the first time. I now understood the depth of the love my own parents felt, the glowing pride, and above all, the worry. The sleepless nights waiting for me to come home made sense. The lectures on safety and responsibility made sense. Because from now on and forever, I was only okay if Henry was okay.

We were lucky. Henry had hardly ever been sick in his life – and his sister is just the same. It’s a little embarrassing, now, to look back on how often my husband and I would congratulate ourselves for having such radiantly healthy children. To us, the absence of fevers and runny noses was almost a kind of personal virtue we could claim.

This feeling only intensified when Robert began working at Seattle Children’s. “I see sick kids there Henry’s age and it just breaks my heart,’’ he told me. “I can’t imagine being in their shoes.” At least we knew we had something to be thankful for, in a way that maybe not all parents do.

Serious illness was something that happened to other people’s kids, until last November.

Henry, who turned 3 in October, was uncharacteristically lethargic – first not really wanting to jump, then run, then walk more than a block or so over the course of about two weeks. He wanted to be carried to the car, and up the stairs. There was no complaint of pain, just a gradual avoidance of most physical activity.

For a week, he’d had a mild but recurring fever. His tummy was a bit bloated, and he was constipated. He seemed pale and out of sorts, not himself. The lymph nodes on his neck felt large to my touch. So I figured he was fighting something off and gave him the extra rest I thought he needed.

On the day his temp spiked up to 102, I ran him over to urgent care after work, just to rule out anything serious. Our doctor looked him over, heard the list of symptoms, and reassured me that Henry was just fighting off a bug. She was on her way out the door, telling us to follow up if he got any worse, when I stopped her and asked her to feel his neck.

She did, then felt his bloated tummy and looked again at his pale face. Finally, she ordered a blood draw – not wanting to take any risks. We drove a block up the hill to the lab at the hospital. Henry asked me to carry him inside; I told him he was a big boy and could walk on his own.

I didn’t know. I didn’t know yet that his marrow was pushing so many immature white blood cells into his bloodstream that his bones were badly hurting. In the lab, I watched his blood fill the vial and thought to myself that it looked thin, almost pink. Not the deep red color I would have expected.

They told us we wouldn’t hear back until the next day, and only if something was wrong. Two hours later, Henry woke suddenly, screaming in pain and distress. Moments later, our urgent care doctor called me from her personal cell and left a message: “The results are back, and you need to get him to Seattle Children’s, right away. Go straight to the ED – they already know you are coming.”

Shock hit me and then the adrenaline surged. We buckled a very sick and very sleepy Henry into the car and drove an endless 25 minutes to the Children’s ED.

Even through the panic, it never occurred to me how serious a situation we might be in. I was so intent on getting him to the place where he could be safe and well again; my mind had no room for anything else. When a doctor came into our room after several more blood tests, did a quick exam on Henry and told us he was concerned about the possibility of leukemia, my whole world fell apart.

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia, they said. We were wheeled upstairs into the Cancer Care Unit, to be admitted right away for at least a week. My parents and stepfather were with us; we were all in shock. Henry, riding on the bed with me, finally began to doze off as we rolled into the elevators well past 2 a.m. to begin our inpatient stay.

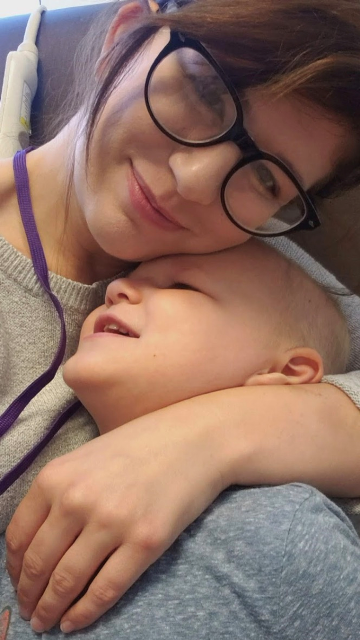

On our first full day, they ran still more tests on Henry to nail down an exact diagnosis. One resident sat with us during a quiet moment after her attending had left. The room was dim and Henry was slumped asleep against me, exhausted and sick. One day later and he could no longer walk, or even stand up on his own without crying in pain. The disease had accelerated.

Into the silence, I asked if a cure wasn’t possible, would we at least be able to manage the cancer, to keep it at bay long enough to give him — as I put it — “a good run?” My voice gave out at the end.

The resident sought out my eye line, waited until I looked up again and gently said, “We intend to cure him.” She paused and added firmly, “I believe we will cure him.”

I sat there holding Henry, crying silently. We had quickly compartmentalized our terror and were so entirely focused on what was next — the next test result, the next procedure, the next foul-tasting medication he needed — that to consider the possibility of a cure was to confront the idea of the disease itself. The disease that might kill our son.

An hour or so later, while Henry still slept, I repeated back to Robert what the resident had said. He covered his face with his hands and sobbed. I held him and cried with him. We were two parents at once confronting the worst possible fear, and allowing ourselves to believe the fear might not come true. Our darling Henry. Our sweet, precious, beautiful boy.

More test results came back and we learned that Henry had the most treatable form of ALL, with only a few cancer cells in his spinal fluid. Survival rates for Henry’s diagnosis are very high; in our heads, we were hopeful. Still, shock and terror persisted in our hearts.

Chemotherapy began, including spinal injections under anesthesia. The first time he went under I held him in my arms and watched his consciousness flutter away. With the help of the nurses, I set him down on the bed just so, and then broke down as I staggered into the adjoining waiting room. Seeing him slip away from me like that…it felt like the very worst fear come true.

But by the end of our weeklong stay, Henry’s leukemia cell counts had plummeted in response to the chemo and he was running, jumping and playing again, eager to get home to his little sister and return to normal life. At 3, he was too young to understand 98% of what was happening. He only knew that he was sick, and needed medicine to get better. That was enough for him.

I was and am so thankful for his lack of comprehension, that we can hold all the fear for him. He can be free of that, at least, through all the rest.

We were discharged and Henry settled joyfully back in at home, but outpatient treatment would continue for many more months. After the first month of treatment, called Induction, they would draw a bone marrow sample and determine if any detectable cancer remained. That difficult first month, filled with steroids that made Henry moody and fiercely hungry at all hours, finally came to an end. The marrow was drawn, and we waited for the call.

Again, I’d compartmentalized the fear to remain functional. So when our doctor called to tell us the result was negative, that Henry was in remission, I was only dimly aware of the tears rolling down my face. I called Robert, who was at home with Henry and my father, and gave them the news. My father wept, and Henry — thinking he was sad or hurt somehow — went to comfort him.

Along with this miracle came other, more challenging news. Thanks to a new study, showing an 8% gap in cure outcomes, those few cancer cells in Henry’s spinal fluid now qualified him for the high-risk treatment plan. This meant more months of treatment, more chemo, more transfusions, more side effects. Tough to swallow, but ultimately the information was empowering and gave us the opportunity to provide Henry with better care.

Therapy marched on with its ups and downs. The weeks and months struggled by. From the beginning, Henry has amazed us all. He has managed to avoid a feeding tube, but for a brief two week period when it was placed preventatively and not really needed. He has struggled with nausea and lack of appetite, but has vomited only rarely, defying all expectations. Even now, as he gets chemo three times a week, he cheerfully raids the cupboards and pesters us for snacks.

We have tried our mightiest to preserve his sense of joy and fearlessness, like when his hair started to thin too badly, and we finally needed to buzz it off. Robert pulled out the clippers; we smiled and encouraged and praised him as the strands fell to the floor. Afterward, we did a grand reveal to show him his own reflection and told him how handsome he looked. Henry grinned at himself in the mirror with pride.

I tucked him into bed that night and turned off the light and shut the door. Then I fell onto my bed and cried for my baby, for the strands of golden baby hair on the bathroom floor. The terrible pain of the metaphor.

Overall, we are fortunate that the side effects have been relatively minimal so far, and that we have been able to maintain some semblance of normalcy as a family. We have struggled mightily at times, in many different ways, but the still-frequent happy moments shine so much brighter and I am deeply thankful for all of life’s beautiful moments.

Thanks to the incredible care at Seattle Children’s, Henry has bloomed like any other 3-year-old might have over these past 10 months. At first, we watched with wonder as through the many hospital visits and interactions with kind and well-meaning strangers, our anxious boy grew more social and more confident. Now, he strolls into the hematology-oncology clinic, familiar with every corner. Everyone there greets him by name.

In addition to their incredible competency and kindness, I truly believe that every member of Henry’s care team wants to see him cured as much as we do. They also want to spare him as much pain, discomfort and fear as possible, whether it’s with supplemental meds or by successfully distracting him with friendly patter, snacks, tablets or toys. As a mother, there’s nothing more I could ask from his medical caregivers.

What I never anticipated, setting out on this terrifying journey, was that Henry would ask us to take him to Seattle Children’s — as when his sister tore apart a train set he’d constructed in our living room. “Daddy,” he said with exasperation, “I want to go back to the hospital.”

Now, almost 10 months since Henry’s diagnosis, less than six weeks of active treatment remain. Then we reach the maintenance phase, and will continue to administer small amounts of oral chemo at home, with monthly labs at the clinic. Life will mostly go back to normal. The kids can go to school. We can take vacations. Take time off that we spend somewhere other than the hospital.

Although the odds of a cure are good, we don’t know yet if Henry will relapse. We don’t know what mid-to-long term side effects of the treatment there may be. While anxiety about the future and the potential for relapse looms, a bone-deep gratitude often overwhelms me too. The feelings are immense and often at odds. It’s a lot to contain in one body and mind. Thankfully, we have each other, and our amazing extended families.

Whatever the eventual outcome for Henry, this fight is changing us forever, in ways we don’t quite understand. But we will continue to cherish the everyday joys, and seek out the silver linings anywhere we can.