At Seattle Children’s, many children and young adults with cancer are finding hope in T-cell immunotherapy – an experimental treatment that boosts a patient’s immune system and uses it to fight a disease.

Seattle Children’s researchers are leading clinical trials in which a patient’s T cells are reprogrammed to express a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) on the surface of the cell. The CAR is like a puzzle piece that’s designed to attach perfectly to a specific antigen or marker on the surface of the cancer cell. When they attach, the CAR T cells attack the cancer cells as if they were fighting an infection.

In just five years, Seattle Children’s cancer immunotherapy program has grown tremendously to include trials that target leukemia, brain and spinal cord tumors and solid tumors. Curious how these clinical trials work? Read on to learn more about the immunotherapy clinical trial process at Seattle Children’s.

Moving research forward, faster

To make novel CAR T-cell immunotherapies readily available for pediatric patients who desperately need them, Seattle Children’s has developed the Immunotherapy Integration Hub (IIH).

“IIH has streamlined the research cycle for immunotherapy by consolidating the necessary expertise and resources, and better defining and organizing the processes involved in translational research,” said the associate medical director of the IIH.

Instead of taking more than 10 years to go from conceptualizing an idea to opening a clinical trial, the IIH is expected to shorten that cycle time to three to five years. If a CAR target has already been proven to work in a certain type of cancer, the timeline to a clinical trial could be just a year or two.

Developing an idea

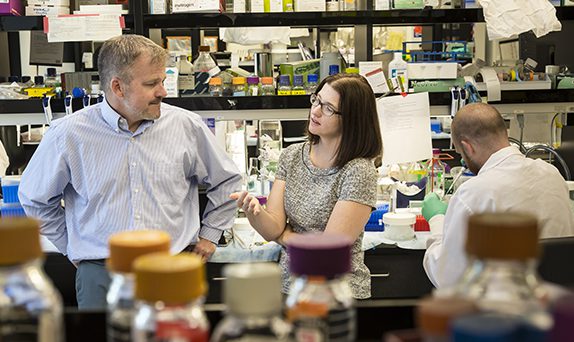

Creating an immunotherapy clinical trial typically begins with the Immunotherapy Research and Development (R&D) team.

“When a principal investigator or other research staff member identifies a promising target for a certain type of cancer, we develop the CAR,” said Dr. Adam Johnson, R&D manager. “We also continuously design methods and technologies to enhance the performance of CARs in our existing clinical trials.”

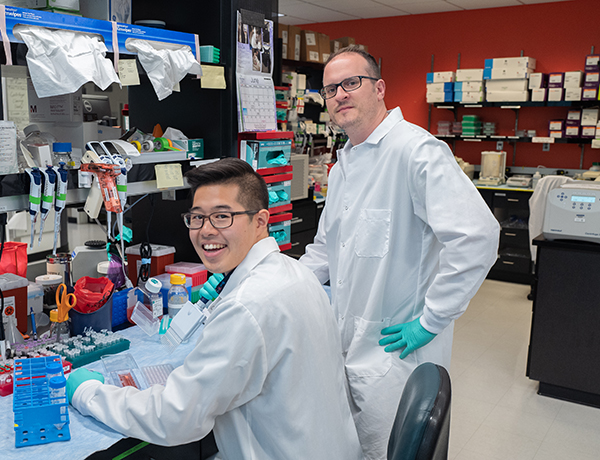

Jason Yokoyama is a research scientist in R&D who specializes in cell culture and helps lead the cellular core of the R&D group.

“Much of my work involves characterizing new CAR T cells by confirming their functionality and evaluating their efficacy,” Yokoyama said. “When we have a strong candidate for a new clinical trial, I work with the preclinical group to move our CAR T cells from the lab to the clinic.”

While work in the IIH is challenging and fast-paced, Yokoyama appreciates how quickly their research is translated to patients.

“We’re helping kids with no other options,” Yokoyama said. “It’s amazing to work in a place where we get to see patients go into remission and know we’re making a difference.”

Getting “safe treatments to more patients faster”

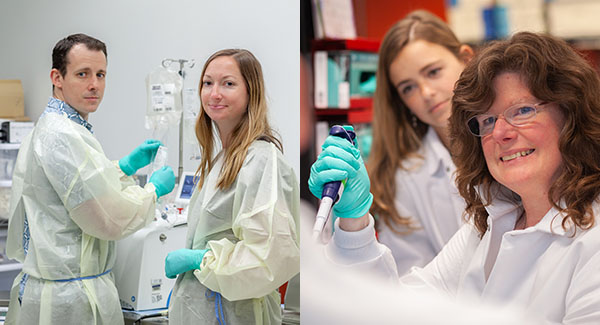

Before newly designed CAR T-cell products are manufactured for clinical use, the Process and Analytical Development team works to improve the production process.

“The patients in our clinical trials need these therapies as soon as possible,” said Dr. Josh Gustafson, manager of Process and Analytical Development. “We work with the Therapeutic Cell Production Core (TCPC) to reduce the cost and time required to manufacture treatments. Ultimately, our goal is to get safe treatments to more patients faster.”

One example occurred when Gustafson and his team worked with TCPC to assess the manufacturing process for the PLAT-02 trial. Together, the two teams developed a new, faster manufacturing process.

Next, the Preclinical Development team steps in to validate the new CAR T-cell therapies for clinical trial. Dr. Karen Spratt, manager of Preclinical Development, and her team work with the product manufacturers in TCPC on a “rehearsal” of the therapy to ensure they have everything ready to make a safe, viable product. They then test the CAR T-cell product’s efficacy, including how well it can identify the specific tumor cell target and eliminate it. The team then submits this data to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) before patients can be enrolled in a clinical trial.

Transforming trials with data

When new CAR T-cell products are developed in the lab, the Immunotherapy Coordinating Center (ICC) assesses them and develops clinical trial protocols so that they can be safely tested in children and young adults.

Additionally, throughout the clinical trial process, the ICC collects, manages and analyzes data in order to answer research questions and ensure data coming out of trials satisfies FDA requirements.

“The only way to transform pediatric cancer treatment is by having data to prove immunotherapy is safe and effective,” says Cristin Gordon-Maclean, director of the ICC.

Cristin says ICC staff members are eager to work on such cutting-edge, state-of-the-art therapeutics designed for the pediatric population.

“Children aren’t always included in clinical trials. So being able to move the needle forward in an area that shows such promise, in a population that is not usually first in line, is really motivating,” she said.

Coordinating care

Heidi Ullom is truly the “Jane of all trades” on the clinical side of Seattle Children’s cancer immunotherapy. As the program’s care coordinator, Ullom begins working with patients and their families as soon as they inquire about Seattle Children’s immunotherapy treatments, collaborating with immunotherapy intake coordinator Grace Mun to collect their medical histories and schedule their initial screening appointments.

Once patients arrive at Seattle Children’s, Ullom helps educate them on their trial protocol and provides an individualized calendar detailing their treatment plan.

“I am privileged that these families — from all over world, who’ve endured years of treatment — let me into this honorable place in their lives and trust me to guide them through treatment,” Ullom said. “No matter what the outcome, their journey is most important. I just ask myself, ‘How can I support them along the way?’”

Learning a patient’s history

Lauren Huang is the advanced practice provider who manages immunotherapy patients’ outpatient care alongside her physician colleagues.

When clinical trial patients first arrive at Seattle Children’s, Huang leads them through a thorough consultation to make sure their condition has not worsened, and they still qualify for the trial.

“It is a multidisciplinary process,” Huang explained. “We work in conjunction with infectious disease, nutrition and pharmacy to make sure we have a full picture of these patients.”

During that first meeting, Huang asks patient families what they know about immunotherapy and explains what their child’s treatment will involve as she guides them through the consent forms for trial enrollments.

“It can be difficult to not promise them a cure, especially because, for many of our patients, there is no other option,” Huang said. “They often tell us ‘We don’t have a choice.’ I can only imagine what that is like for them.”

Collecting patient cells

For all patients enrolled in one of Seattle Children’s cancer immunotherapy clinical trials, one of the first major treatment milestones is apheresis, a process where blood is removed by a machine that separates the liquid part of blood from the blood cells. White blood cells are collected while the rest of the cells are returned to the patient along with their blood plasma. The procedure can take anywhere from two to five hours.

Because apheresis is a specialized procedure using unique equipment, it requires assistance from Bloodworks Northwest nurses.

“After seeing so many patients go into remission, the nurses from Bloodworks Northwest look forward to coming here, even volunteering on their days off. It’s wonderful to see how invested they are in the program and how much pride they take in it.”

Addressing unique needs

One role created to accommodate the increasing number of cancer immunotherapy patients — and their unique needs — is the program’s designated social worker Michelle Bayard.

With 20 years of experience in general social work, Bayard’s new role is to identify and support the psychological, social and emotional needs of Seattle Children’s immunotherapy patients and their families.

“For many of these patients, this is their last treatment option so I’m meeting them at a critical point in their lives,” Bayard said. “They’re often very hopeful, but also very concerned about the outcome.”

Working closely with Ullom, Bayard helps patient families from around the world get to Seattle Children’s safely and ensures they have the resources they need once they arrive. This often includes coordinating housing and transportation and providing information about Seattle.

As an increasing number of international patients enroll in Seattle Children’s immunotherapy clinical trials, Bayard works with interpreters, helps families find foods that are familiar to their culture and connects them to other local families from their home country.

“I feel fortunate to have the opportunity to become deeply involved with these families and help them through this experience,” Bayard said.

Helping patients thrive through treatment

Cancer immunotherapy patients often come to Seattle Children’s in less-than-optimal condition. But a team of eight specialized nutritionists helps them recover and ensures they are strong enough to handle immunotherapy.

“Statistics prove patients who are well nourished tolerate treatments better and have superior outcomes,” said Mary Verbovski, a clinical dietitian. “They have a lower risk of infection and can heal faster.”

Oncology and bone marrow transplant dietitians perform a comprehensive baseline nutrition assessment on all new oncology patients. This includes a close look at a patient’s growth and weight history; diet history; food allergies and current nutritional status. Then, they develop an individualized plan for each patient, in collaboration with the patient and their family.

“Some patients come to our program weak and severely malnourished,” said Kathy Hunt, supervisor of the oncology and bone marrow transplant dietitians. “They may not have received optimal nutrition during years of treatment, and now they are here for this life-saving therapy.”

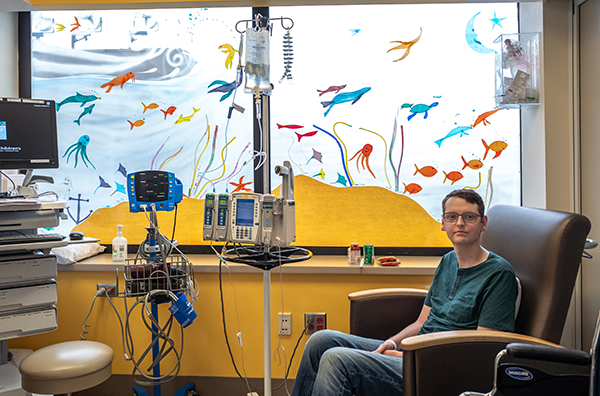

Kevin Bonko, a 23-year-old patient in PLAT-03, relied on Seattle Children’s dietitians when he became malnourished.

“They gave me recipes and worked with me to hit my diet goals,” Bonko remembered. “They helped me pull myself out of a deep hole.”

Manufacturing CAR T-cells

Patient T cells are collected during apheresis and sent to Seattle Children’s Research Institute’s Therapeutic Cell Production Core (TCPC) to be reprogrammed to fight the patient’s cancer.

TCPC’s Cell Production group isolates the T cells and engineers them to express a CAR on the surface of the cell. The CAR is like a puzzle piece that’s designed to attach perfectly to a specific antigen or marker on the surface of the cancer cell.

When they attach, the T cells attack the cancer cells as if they were fighting an infection.

The newly programmed T cells are grown to multiply into billions of new cells to be infused into the patient.

“We love to hear from the clinical team when a patient has gone into remission,” said Christopher Brown, director of GMP Cell Production. “It’s so rewarding to be part of a team working to give these kids a chance to have a great life.”

Providing interim treatment

While their T cells are being reengineered, some patients receive chemotherapy to help keep their cancer at a low level before their T-cell infusion.

Typically, patients who are not local will return home during this time.

Once their reprogrammed CAR T cells are ready to be infused, patients return to Seattle Children’s, are reevaluated and are treated with lympho-depletion chemotherapy for four days. This chemotherapy helps decrease the number of normal T cells in the body to make room for the new, cancer-fighting CAR T cells.

“Every patient we see has been through a lot already, and immunotherapy provides new hope for them,” said infusion nurse Addie Buglione. “It is exciting and rewarding to be able to deliver this care that could finally provide a cure.”

Getting to the big day

There’s an unmistakable energy in the cancer infusion suite when a patient is about to receive their reprogrammed T cells. Some families throw a party, others pray, but there is always a palpable sense of hope.

“I love T-cell day!” said Ullom. “It’s a simple procedure but a momentous occasion. These families have come so far, and I’m honored to be a part of it.”

CAR T cells, stored in large, round freezers and cooled with liquid nitrogen, are transported from the TCPC lab to the clinic by TCPC staff members. The cells are carefully removed from the freezer and warmed in a controlled thawing machine.

Before the infusion, patients receive Tylenol and Benadryl as a precaution to protect them from a potential allergic reaction to the preservative their T cells are frozen in. While all patients react to these medications differently, Ullom said many, like Bonko, fall asleep.

“For some I think it’s a way for them to cope. They shut down and go inside themselves,” she said. “These families come to us with hope, but they’re also skeptical. They’ve been on the wrong side of the odds so many times, it’s common for them to be a little guarded.”

For TCPC team members, this step is the most meaningful part of their work.

“It’s rare, in this type of job, to be able to see your work directly applied to a patient,” said Lauren Barry, a research scientist II on the TCPC Manufacturing team. “It makes me step back and remember what’s important when I’m working in the lab.”

A nurse infuses the CAR T cells directly into the patient’s blood through a Port, PICC line or Hickman catheter over one to two minutes. The patient is then observed for three to six hours to watch for side effects before they are released from the hospital.

The hope is their new T cells will begin finding and destroying cancer cells within a week.

Providing care after infusion

Clinical staff members closely monitor immunotherapy patients for at least 28 days after their infusion, watching for cytokine release syndrome (a form of systemic inflammatory response), abnormal organ function, low blood pressure, trouble breathing or neurologic symptoms.

When these symptoms occur, patients must be admitted to the hospital. Sometimes, they require treatment in the intensive care unit.

Most patients have a fever by day 14. This is a good sign the T cells are working.

“It can be a very emotional time for families who are waiting to learn if the therapy worked,” attending physician Dr. Julie Rivers said. “For many of them, this is their last hope for a cure.”

After three to four weeks (depending on the trial), patients who are stable are typically able to return to their primary healthcare team for further evaluation. Nonetheless, Seattle Children’s immunotherapy providers continue to follow these patients for months, if not years.

Constantly improving

An important driver of Seattle Children’s cancer immunotherapy program is the “feedback loop.” The Correlative Studies group collects patient research data that is shared with researchers and used to improve treatments for future patients.

Correlative Studies analyzes the molecular markers on patient specimens (blood, bone marrow, spinal fluid and tumor biopsies) before and after they are treated with CAR T cells. The goal is to answer key questions like: how long do the cells grow in the patient; how do the cells move through the patient’s body and how efficiently are they killing cancer cells.

“Our goal is to make this an iterative process,” said Olivia Finney, manager of the Correlative Studies lab. “Let’s not stop until we have a treatment that can completely replace chemotherapy.”

Looking long-term

Patients in Seattle Children’s immunotherapy clinical trials are followed by researchers for years after they leave the hospital. Research associates, like Katelyn McLeod, are responsible for monitoring patients CAR T cell persistence, delayed adverse effects and their overall physical health.

“It’s rewarding to see kids who are alive and doing well years after their therapy,” McLeod said.

If you are interested in supporting the advancement of immunotherapy and cancer research at Seattle Children’s, please visit our donation page.