Every year, over 1.2 million people continue to be infected by HIV. Of these, about 160,000 are infants that contract the virus from their mother. Without treatment, a third of these infants die by their first birthday, and half of them do not make it to age 2.

Thanks to programs that identify and treat HIV-infected mothers and children, the number of deaths in children has decreased nearly 50% since 2010. Despite this success, HIV infections in infants remain persistent primarily because not all mothers know if they are infected or, for a variety of reasons, are unable to adhere to taking the antiretroviral medications they need to prevent transmission.

To close the gap, scientists at Seattle Children’s Research Institute are looking for new clues in an important indicator of overall infant health – a baby’s developing immune system and microbiome. Ongoing research not only examines how an infant’s microbiome can evolve to help protect against HIV infection, but also what factors, such as diet, alter an infant’s susceptibility when exposed to HIV through their mother’s breast milk.

Immune activation, HIV and the infant gut

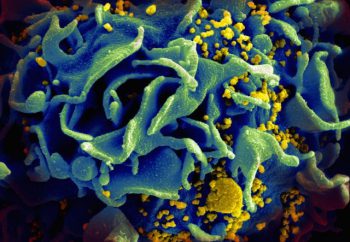

The state of an infant’s immune system is especially important in HIV infection. A highly activated immune system, or immunity, accompanied by high levels of inflammation offers an attractive target for the virus to take hold. Since an infant’s immune system continues to develop after they are born, the foods they eat and the environment they are exposed to can shape how the immune cells in their bodies behave.

Dr. Heather Jaspan of Seattle Children’s Center for Global Infectious Disease Research believes a better strategy to protect infants from HIV will surface from determining the link between the infant gut and immunity. She has spent the last decade establishing cohorts of infants in South Africa and Nigeria to study the developing infant gut and its role in HIV transmission.

“The overriding theme from my work in Africa is that the microbiome, which is largely influenced by feeding in infants, is very important in determining immunity and inflammation,” she said. “Where with other infections you want immunity and inflammation to help you fight infection, an activated immune system is exactly what HIV likes to infect.”

Breastfeeding paradox

When Jaspan first started research in South Africa, she would drive from shack to shack to collect samples from newborns. Now, mainly operating out of a clinic in Cape Town with a team of clinical staff, she follows infants for several months after birth in order to determine which factors of infant feeding can make a baby exposed to HIV either more or less susceptible to infection.

Most infants who become infected with HIV are not infected in the womb, but during breastfeeding. Yet if a breastfeeding mother is not taking medication to suppress the virus, there is only a 15% chance that their infant will be infected. Despite constant exposure to HIV through milk, infants are still partially protected from infection.

Even more puzzling, infants who are exclusively breastfed from HIV-infected mothers, meaning breast milk is their only source of nutrition, have a lower chance of becoming infected with HIV than infants who are fed with a combination of breast milk and other foods like formula, cereals and water.

“That seemed really odd because the natural assumption was that infants just getting breast milk from infected mothers would be exposed to more HIV. My research started to focus on understanding what makes infants more protected when they are only fed breast milk,” Jaspan said.

According to Jaspan, one explanation for why exclusive breastfeeding protects infants from HIV may lie in breast milk’s effect on the infant’s immunity. Another possibility is that a component found in the non-breast milk foods alters the infant’s immunity.

“If we can first determine the protective mechanism benefiting babies exclusively fed breast milk, we can design better prevention strategies, such as a vaccine, to offer mixed-fed infants the same protection,” she said.

Possible link to mold toxin found in mixed-fed infants

A recent collaboration between Jaspan and the lab led by Dr. Don Sodora, a principal investigator now with Seattle Children’s as part of the joining with the Center for Infectious Disease Research, zeroed in on one possible link between infant feeding practices and HIV infection.

Led by Dr. Lianna Wood, then a graduate student in the Sodora Lab, the study set out to identify associations between different infant feeding patterns and CD4 T cells, the immune cell that HIV primarily infects.

Using samples from one of Jaspan’s cohorts in South Africa, Wood tracked infants in the study for several weeks. She examined the data collected on how the infants were fed to explore whether CD4 T cells in exclusively breastfed infants were more or less likely to be targeted for infection by HIV. After analyzing the blood from these infants over time, the researchers discovered something striking. Low levels of a fungal toxin, known as ochratoxin A (OTA) were linked to feeding infants with foods other than breast milk.

Ochratoxin A and HIV

Produced by molds found commonly in the environment, OTA contaminates soil and water, as well as a variety of agricultural products like cereals and fruits. While OTA levels in the two groups of infants were similar at 2 weeks old, OTA levels were significantly higher in later weeks in the infants who were not being breastfed.

“This indicated that as infants switched to, or continued receiving food other than breast milk, the levels of OTA in their blood increased,” Wood said.

Subsequent analysis sought to understand whether the low levels of OTA observed in the mixed-fed infants influenced CD4 T cells and possibly HIV. To address this question, the researchers compared levels of OTA in infant blood with different protein markers on the surface of CD4 T cells.

These markers influence the function of these T cells as well as how susceptible they are to HIV infection. They found that levels of OTA in plasma correlated with an increase in several of these markers. Among these was an increase in CD4 T cells with CCR5, which is one of the two proteins used by HIV to infect T cells. In a separate paper, Wood, Jaspan and colleagues found these T cells are also increased with non-exclusive breastfeeding.

“One hypothesis we can glean from this research is that babies having OTA in their blood at certain levels may make their immune system activated and thus, makes them more susceptible to HIV,” Jaspan said.

Correlations may lead to protective vaccine

While the findings offer a possible link between infant feeding practices and HIV infection in a population that is particularly affected by infant AIDS, more research is needed to identify the source of OTA. Longer-term studies may also inform interventions that promote the development of healthy immune systems in these infants.

“Antiretroviral medications do a very good job at protecting infants who are breastfed from HIV-infected mothers,” Jaspan said. “But because some mothers aren’t able to take these medicines everyday as required, they are not foolproof methods in preventing transmission of HIV to the child.”

Beyond the infant gut, Jaspan also studies HIV and immunity in adolescent females, as well as how other vaccines given in infancy impact HIV susceptibility.

“I hope our research will one day lead to definitive correlations between the microbiome and immune protection that we can then look to mimic in a vaccine that will more reliably protect babies and young women from HIV infection,” she said.