When 11-year-old, Giorgia Graham, told her parents her cheek was going sporadically numb, they thought it was because she banged her face playing tag.

But when the numbness kept coming back, her parents realized it was something more serious. They discovered Giorgia was having seizures when she experienced a grand mal seizure sleeping one night with her mom while her dad was traveling out of the country. Though the seizures remained mostly isolated to Giorgia’s face, some, like this one, took over her entire body and caused her to lose consciousness. At worst, she was having more than 60 seizures a day.

“When medications didn’t stop the seizures, Giorgia’s mom, Christina, and I knew brain surgery was our only hope,” said Nick Graham, Giorgia’s dad. “That’s when we came to Seattle Children’s for a second opinion to see if surgery was possible.”

Making things more complicated, a full workup of diagnostic tests couldn’t pinpoint the source of her seizures. That meant her doctors couldn’t see precisely where the seizures were starting or know where to operate.

But her care team at Seattle Children’s Neurosciences Center didn’t give up — they doubled down.

Dr. Rusty Novotny and Dr. Jeffrey Ojemann proposed an innovative solution. They would use a robot to guide thin wires into Giorgia’s brain, monitor its electrical pulses and find out where the seizures originated. Then they would use laser ablation to deactivate that part of the brain.

“I never would’ve thought we’d be excited for our kid to undergo a new type of brain surgery,” Graham said. “But Giorgia needed to get back to playing softball and basketball, riding horses, and to just being a kid.”

Epilepsy Program’s comprehensive evaluation

When Novotny first saw Giorgia during an appointment in November 2019, she, like a subset of children with epilepsy, still experienced daily seizures despite treatment with multiple anti-seizure medications.

“About 70 to 80% of children with epilepsy have seizures that respond to medication,” said Novotny, a pediatric neurologist and director of Seattle Children’s Epilepsy Program. “Roughly 20 to 30% of children do not see improvement with current medications. Once we try up to two drugs without any benefit, we’ll go through a comprehensive evaluation to see if surgery is an option.”

Seattle Children’s is the only program dedicated exclusively to pediatrics in the Northwest accredited level 4 by the National Association of Epilepsy Centers (NAEC). Only centers with this designation have the diagnostic tools and expertise to evaluate a patient and perform a broad range of complex surgeries to treat epilepsy.

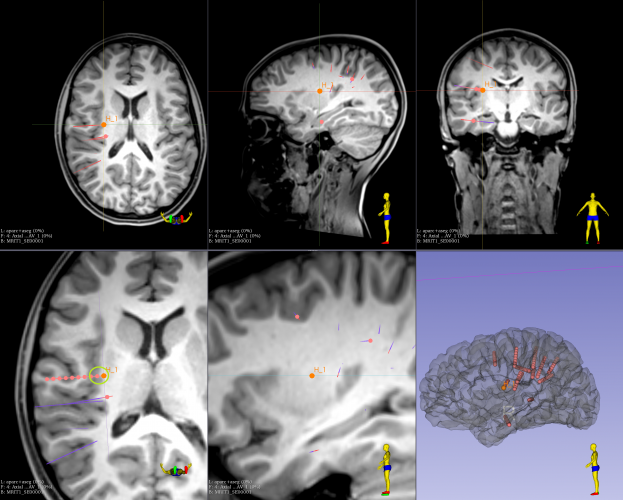

Most evaluations include several advanced neuroimaging procedures to provide detailed information about the brain’s structure and function to locate the source of the seizures down to a few millimeters. By using a combination of techniques, Seattle Children’s has shown it can make more accurate diagnoses and improve care.

“Imaging has revolutionized our ability to find an underlying cause when it had not been possible before,” Novotny said. “To move forward with surgery, you really want to know: one, do the seizures originate from only one part of the brain, or what we call focal seizures, and two, can you remove or deactivate the abnormal area while preserving critical functions like the ability to think, move, see and speak.”

New imaging tools pinpoint surgical target

At Seattle Children’s, Giorgia underwent a series of procedures as part of her initial evaluation. While an electroencephalography (EEG) over her scalp confirmed suspicious activity in one area of Giorgia’s brain, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan didn’t uncover any major physical differences in the same region. Other procedures part of the evaluation also gave a general sense of the seizure origin, but the evaluation as a whole didn’t offer the definitive target the team needed to proceed with surgery.

“We had the zip code of where the seizures were coming from, but we really need to get to down to the street level before we do invasive surgery,” said Ojemann, Giorgia’s neurosurgeon and a senior vice president and surgeon-in-chief at Seattle Children’s.

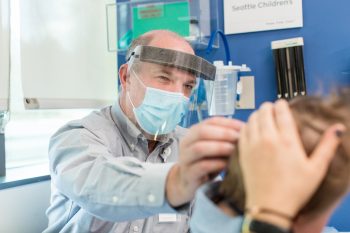

Hoping to get a better target for surgery, the team turned to a newly added technology in their toolbox, robotic-assisted stereotactic EEG, or SEEG. In SEEG, surgeons use a robotic arm to guide multiple very fine wires attached to electrodes into the region of the brain suspected for the seizures. The electrodes then record seizure activity over several days.

The robotic procedure is minimally invasive compared to standard SEEG approaches that require an significant operation in which the scalp and bone are removed and the electrodes are placed by hand.

“The beauty of using the robot is that it lets us place more electrodes in the brain in a safe and time efficient manner, so we can be much more expansive in our sampling,” Ojemann said. “In return, we can pinpoint with much higher certainty the location in the brain responsible for the seizures.”

Laser surgery offers ideal approach

In Giorgia’s case, the SEEG zeroed in on a very small area, deep in her brain. Surrounded by blood vessels and very near the part of her brain responsible for her motor function, Ojemann recommended another minimally-invasive approach called laser ablation to remove that area of the brain.

An early adopter of laser ablation for epilepsy and brain tumors, Seattle Children’s remains among the few children’s hospitals in the U.S. to offer the therapy which uses a MRI-guided laser probe to deliver light and heat to destroy the unwanted cells. It’s highly effective for exactly the type of abnormality the team uncovered in Giorgia.

Ojemann and her Neurosciences Center team hoped that targeting the abnormal brain tissue with this laser surgery would put an end to her worsening seizures.

“You can’t treat every condition with laser ablation and in many cases, especially if the problem is near the surface, it’s safer to do an open craniotomy,” Ojemann said, describing the more traditional approach to epilepsy surgery. “Laser ablation makes a lot of sense if you’re going deep into the brain, it’s a small target and you know where that target is.”

The procedure takes place while the patient is in a MRI scanner, so that surgeons can use real-time images to ensure that the laser probe is directed at the desired area. The actual treatment lasts less than a minute and it only requires one stitch when it’s all done. Most patients can go home within one to two days.

On the day of Giorgia’s surgery, March 13, 2020, the team went one step further to confirm they had the right target. Before placing the laser probe, they used the SEEG to sample the area once again. Confident they had the source of the seizures, Ojemann proceeded with the laser ablation treatment.

With two small treatments, less than a centimeter each, the seizures that afflicted Giorgia over the last several years stopped.

Treatment tailored to the patient

Today, over nine months later the results still amaze her parents.

“Her seizures stopped and, hopefully, are gone for good,” Graham said. “She has slowly weaned off two of the three medications she was taking which has significantly decreased the side effects she was experiencing. She was on some pretty heavy meds and it is nice to put them in the rear view mirror. Most important, Giorgia is living like a kid again, playing sports and riding her bike with friends.”

Ojemann said Giorgia’s case highlights many of the reasons families choose Seattle Children’s.

“Not only did we provide an innovative solution by combining two minimally invasive techniques to target and treat the cause of her seizures, we brought many different pieces together to arrive at that solution,” he said. “Our approach in the Epilepsy Program, and really one embodied by all of Seattle Children’s, is that we’re going to individualize the treatment and we want to have as many tools as possible to do that. We don’t lock ourselves into only doing it one way. We want to be safe, but also flexible in our thinking so that we can tailor our approach to be most helpful for that child.”

Nick and Christina trusted they were placing their daughter’s care in the best hands possible.

“Dr. Novotny and Dr. Ojemann gave us complete confidence. They spent hours on the phone, answering our questions and explaining the data they gathered,” Graham said. “I consulted other top children’s hospitals, and their doctors all told me the same thing: If this was our daughter, we’d take her to Seattle Children’s.”

The team of the future

Seeing the power of innovation first-hand inspired the Grahams to help bring this transformative care to more children.

The family made a donation to fund a new post-doctoral fellowship at Seattle Children’s now held by Dr. Alexander Doud, a neuroscientist and bioengineer who is bringing innovations from the lab to the clinic, and moving Seattle Children’s closer to being able to cure every child with epilepsy.

“If our family can help with that, or even help just one more child have results like Giorgia’s, it will be the best money we ever spent,” Graham said.

Other research driven by the SEEG and epilepsy surgery populations at Seattle Children’s is helping doctors better understand brain recovery and brain function. By studying small pieces of removed brain tissue, the team has also uncovered new genetic causes at the root of many of the brain abnormalities found in childhood epilepsy. This has led to an early phase clinical trial of a targeted therapy aimed at addressing the root cause of many seizure disorders in children.

“We understand better the risk of untreated epilepsy, including its impact on quality of life, but even sudden death from epilepsy,” Ojemann said. “We’re finding new ways to be as aggressive as possible while being as safe as possible in treating ongoing seizures. Everything from our ongoing research to the breadth and expertise of our team, our imaging capabilities, and ensuring every child gets a full neuropsychological assessment contributes to making the outcome as patient focused and positive as possible.”