In recognition of Mental Health Month, On the Pulse will be sharing valuable resources and inspiring patient stories each week to guide individuals and families struggling with mental health issues and help destigmatize the topic of mental health in our society.

In recognition of Mental Health Month, On the Pulse will be sharing valuable resources and inspiring patient stories each week to guide individuals and families struggling with mental health issues and help destigmatize the topic of mental health in our society.

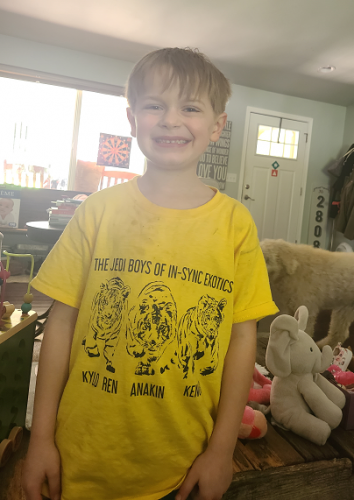

One late afternoon in April, Jessie Early noticed something was wrong her with 7-year-old son, Rohan.

He stopped eating, was withdrawing, and exhibiting suicidal thoughts.

Extremely concerned, Early rushed her son to Seattle Children’s Emergency Department (ED), as recommended by Rohan’s psychiatrist at the time.

Within just a few minutes in the waiting room, Rohan was sent directly to one of the patient rooms for evaluation.

What could have been a stressful and trauma inducing experience for Rohan, Early was pleasantly surprised with the attentiveness and support that the staff provided her son.

“There was always someone there to answer our questions,” Early said. “It made it so we were relaxed and informed. Staff would ask him questions in a respectful and polite way, even though some of questions were difficult for him answer. They were there for us every step of the way.”

Support from every angle

Rohan is one of the many patients at Seattle Children’s that has benefited from the Emergency Department Extension (EDE) at Seattle Children’s.

Rohan is one of the many patients at Seattle Children’s that has benefited from the Emergency Department Extension (EDE) at Seattle Children’s.

The EDE is a new program providing rapid access to brief care for children and families experiencing a mental health crisis. Accessed after an ED visit as an alternative to inpatient hospitalization, it is designed for children who are in crisis but are not at imminent risk of harm. These crisis situations include suicidal thoughts or behavior, thoughts about hurting others, or sudden change in mental health status. The EDE fills a gap by providing rapid access to evidence-based mental health care. Additionally, families in the EDE receive case management support to increase linkage to ongoing care in the community.

“I was impressed by how thorough the entire process was,” Early said. “Everyone from the security team, nurses, to the mental health professionals, were helpful, kind, and nurturing.”

At first, Early couldn’t help but be worried about how the entire situation would be handled.

“I was reluctant to even admit him to the hospital,” she said, “but once we arrived I instantly felt reassured that Rohan was in good hands.”

Before Rohan was discharged, Early received the support tools needed when dealing with a mental health crisis.

“They got us fully onboard and made it easy for us to leave, as we were set up with tools and promised further consultation after we went home,” Early said.

Within just a couple of days of leaving the hospital, Early received a call from Seattle Children’s.

“It was amazing to see how quickly they got back to us,” she said. “The staff would call and email us, helping sort out his mental health needs moving forward.”

Staff took an active approach, working closely with Rohan’s primary care provider, psychologist and psychiatrist.

“I was so impressed by the level of detail that went into helping Rohan,” Early said. “It was more than I could’ve ever imagined.”

Adjusting in the era of COVID-19

The idea for the EDE arose in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic amidst initial concerns that Seattle Children’s ED would face a surge in COVID-19 cases.

The idea for the EDE arose in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic amidst initial concerns that Seattle Children’s ED would face a surge in COVID-19 cases.

Seattle Children’s mental health teams sought to innovate and expand on the model of the Behavioral Health Crisis Care Clinic (CCC) already in place to intercept and prevent mental health crises inside and outside of the hospital.

Established in 2018 by Dr. Elizabeth McCauley with a grant from a generous family foundation, along with support from Tinte Cellars, the CCC at Seattle Children’s was the first real attempt to provide an alternative to hospitalization, primarily around suicide ideology. The effort later expanded beyond suicide, to include other mental health needs such as anxiety, developmental disorders and behavioral crises. Telehealth services were later incorporated to help families receiving care outside of Seattle Children’s access behavioral health resources.

“With the onset of COVID-19, we knew that existing community resources would not be operating as usual,” said Erika Miller, manager of mental health consultation at Seattle Children’s. “Additionally, with the increase in stress and loss of school structure we sensed our families would have more challenges in accessing behavioral health resources in a state where they are already stretched.”

Anticipating this impact, the team created the EDE, which accepts patients like Rohan, seen at Seattle Children’s ED, or children seen in community EDs, that may have a gap in access to resources. A mental health evaluator triages the case, determines what is driving the crisis, and what immediate resources are needed. They then provide follow-up phone calls to families back at home to offer further coaching and support in managing or calming the crisis.

This follow up with the family and case management continues until they are connected with ongoing community resources. The EDE can also link these families to brief crisis intervention provided by Seattle Children’s outpatient psychiatry and autism teams to focus on acute suicide, aggression, behavioral outbursts or debilitating anxiety concerns that might otherwise lead to an inpatient admission.

To date, Seattle Children’s has helped more than 50 families, like Rohan’s, get the care they need without hospitalization through the EDE model.

“With a son who has many mental health needs, I’m grateful that Seattle Children’s offers such a program,” Early said. “It was positive experience for not only me, but Rohan as well, which as mother, is most important to me.”

If you, your child or family needs help right away, call your county’s mental health crisis number. In King County, call 866-427-4747. You can also text HOME to 741741 or call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, 800-273-8255, from anywhere in the U.S. If you or a family member has a problem with a substance use disorder, please consider calling the Washington Recovery Help Line, 866-789-1511.