It’s holiday time in the Louden household. However, this year is unlike any other. For the first time in 11 years, 17-year-old Amber Louden will be able to join her family at the Thanksgiving table and indulge in some of her favorite dishes pain-free.

It’s holiday time in the Louden household. However, this year is unlike any other. For the first time in 11 years, 17-year-old Amber Louden will be able to join her family at the Thanksgiving table and indulge in some of her favorite dishes pain-free.

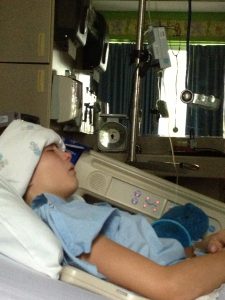

“I remember Thanksgiving two years ago; I ate so much food that I ended up in the hospital because of the horrible pain I was in,” said Amber. “Last year, I didn’t even get a chance to sit at the dinner table because I spent the holiday in the hospital where I stayed for 12 days.”

Amber’s decade-long battle with chronic pancreatitis prevented her from partaking in cherished holiday traditions.

It may be surprising that these traditions and the root of Amber’s struggle with pancreatitis share one common factor — and that happens to be family.

The rise of an uncommon disease among children

Lavinia Louden said her daughter’s health and energetic spirit spiraled downhill ever since Amber was first diagnosed with pancreatitis when she was 10 years old.

Pancreatitis is a disease that occurs when the pancreas becomes inflamed and internal enzymes irritate and damage the organ. Previously, it was thought to primarily be triggered by physical trauma, specific viral infections, some medications or ingestion of a toxin.

“It’s widely known that alcohol and smoking are easily identifiable risk factors in adults who develop pancreatitis,” said Dr. Matthew Giefer, director of gastrointestinal endoscopy at Seattle Children’s who would later treat Amber for her condition. “Although pancreatitis was considered rare among children because it’s uncommon for them to experience exposure to the known risk factors, recent studies have shown that the number of pediatric pancreatitis cases has increased. Children are now susceptible to the disease almost as often as adults, which is approximately 1 in 10,000. But the reason behind the increased prevalence was unknown.”

For Amber, the cause of her condition was also initially unknown. But one thing her family was sure of was that they needed to move from the small rural town in Kansas where they lived to be closer to the medical attention that Amber desperately needed.

A decade of distress

In 2011, the Loudens packed up and moved from the mid-West to the West coast to be closer to a children’s hospital.

“One of the main reasons we moved to Washington State was because we needed better access to the best medical care when Amber needed it,” said Louden. “I knew Amber needed to be seen at a children’s hospital as her condition progressed.”

When the family settled down in their new hometown of Bellingham, Washington, Louden was able to initially manage Amber’s sporadic bouts of abdominal pain and nausea at home. However, as time went by, the pain Amber experienced was no longer something she could endure.

When the family settled down in their new hometown of Bellingham, Washington, Louden was able to initially manage Amber’s sporadic bouts of abdominal pain and nausea at home. However, as time went by, the pain Amber experienced was no longer something she could endure.

In 2012, Louden was referred to Giefer at Seattle Children’s to take on Amber’s care.

“When I met Amber, she was having episodes of pancreatitis,” said Giefer. “While her quality of life remained fine at the time, I suggested she undergo an ERCP or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.”

An ERCP is a form of therapy in which a doctor inserts a long, flexible tube with a camera attached to it down a patient’s throat to their stomach to help diagnose and treat certain problems in the digestive tract, liver, bile ducts and pancreas without the need for traditional surgery. In Amber’s case, stents were inserted into her narrowed bile ducts to hold them open to prevent further blockage and inflammation.

Seattle Children’s has the only pediatric ERCP and therapeutic endoscopy program in the Pacific Northwest. Giefer, a specially trained pediatric endoscopist, is an expert in accurately diagnosing and managing the most complex gastrointestinal and pancreatic issues in kids.

“The procedure helped clean out my bile ducts to stop the inflammation in my pancreas that was causing all my pain,” said Amber. “At first, getting the ERCPs decreased my amount of hospital stays.”

However, over time Amber’s condition intensified and it became clear she needed another treatment option.

“It came to the point where I was feeling excruciating pain every single day,” said Amber. “It gradually got worse and worse as time went by.”

The agonizing pain puts life on hold

While Amber’s friends were sharing photos on their Instagram at school dances or football games, Amber would be stuck at home in bed reeling from pain and nausea.

“I missed the last half of freshman year and all of sophomore year,” said Amber. “I was lucky if I could go to school for an hour. I couldn’t stay away from my house for more than an hour or two because I would start feeling nauseated. The illness literally controlled my life.”

Missing school and activities with friends was one thing; missing special holidays and occasions with family was another.

“There were years I missed birthday parties, Halloweens, and almost one Christmas,” said Amber. “Aside from ending up in the hospital after Thanksgiving, I was also in the hospital during New Years.”

Amber’s pain reached its peak during what was supposed to be a relaxing summer vacation to Maui with her family in 2015.

“I had a bad inflammation attack during the trip,” said Amber. “From then on, it seemed that the attacks would happen more frequently.”

Amber did her best to take her mind off the pain by staying active. After being discharged from a hospital stay, she even competed in a Taekwondo tournament and took the second place medal.

However, it eventually got to a point that was almost unbearable.

“Dealing with my pain became more difficult. In a matter of six months, I had five ERCPs,” said Amber. “But I think the hardest part of it was my frustration that my mom had to put up with. She could only do so much.”

Fearing the next step

In the summer of 2016, Amber and her mom turned to Giefer for other options.

“Dr. Giefer recommended a couple different options for surgery,” said Amber. “Out of those options, there was only one that would completely get rid of the problem once and for all.”

Amber would need to undergo a total pancreatectomy and islet auto-transplant. This surgery involves removing the pancreas, which is then broken down into its components with the islets separated out. The islets are then injected into the patient’s liver. If successful, the islet cells in the liver will produce insulin to keep blood sugar levels normal, supported with supplemental insulin injections if necessary.

As chronic pancreatitis and the need for a total pancreatectomy and islet auto-transplant procedures is very rare in pediatric patients, few children’s hospitals perform the pancreatectomy procedure.

Therefore, Amber was referred to a children’s hospital in Minnesota that specializes in the complex procedure.

“I was intimidated about how long and extensive the surgery would be, but I knew that if I didn’t do it, there would be no chance to have my life back,” said Amber. “If I waited, I knew things would get worse.”

Finding relief after a difficult journey

After the long-awaited surgery that would cure her from the pain that plagued her for most her life, Amber felt relief.

“I felt the change just two weeks after the surgery,” said Amber. “I couldn’t believe it.”

“I felt the change just two weeks after the surgery,” said Amber. “I couldn’t believe it.”

Having had formed a close bond to Giefer over the past five years, Amber and her mom stayed in touch with him on Amber’s progress through videos and text messages.

“Dr. Giefer is such an exceptional and genuine person, not only as a doctor, but as a person overall,” said Amber. “He’s very caring and even checked up on me while I was in Minnesota. I remember getting a text from him right after I told him about my surgery saying, ‘I’ve always known you to be very optimistic, but I’ve never seen you this happy before.”’

Seeing the transformation in Amber was rewarding to Giefer.

“I was glad to see how well Amber was doing,” said Giefer. “It was extremely gratifying to know that she could go on with her life both happy and healthy.”

It runs in the family

Family plays a pivotal role in the way a child develops in life. Whether it’s instilling a certain set of cultural values, passing down traditions, or preferences for a specific cuisine.

“My mom cooks a lot of Filipino food,” said Amber. “I love eggplant and there’s one traditional dish she makes with it, but I couldn’t enjoy eating it because of how sick my illness would make me feel.”

Beyond the impact family might have on a child’s food palate, inheriting specific biological traits, including medical conditions, can be common.

When Amber was recovering from her surgery in Minnesota, Giefer published research results that provided vital answers and a small glimmer of hope to pediatric patients like Amber suffering from pancreatitis.

In May, his study published in The Journal of Pediatrics suggested that early-onset pancreatitis in children is strongly associated with certain genetic mutations and a family history of pancreatitis.

Giefer and colleagues analyzed 342 children ages 0-18 with acute recurrent pancreatitis (ARP) and chronic pancreatitis (CP). Three age cohorts were examined: children ages 5 and below, 6 to 11 and 12 to 18. The youngest cohort of children, ages 5 and below, was defined as having early-onset pancreatitis.

“Determining the underlying causes of the disease in children has been challenging,” said Giefer. “This study allowed us to test and evaluate the association between age of onset and characteristics of patients with ARP and CP.”

The most significant findings of the study emerged from the youngest cohort. In patients ages 5 and below with early-onset pancreatitis, 71% possessed at least one pancreatitis-associated gene mutation that was likely inherited.

“These results are incredibly significant for patients like Amber who suffer from severe cases of pancreatitis,” said Giefer. “A delay in diagnosis is one major issue we’ve seen in children, so looking at family history of the disease may help providers spot the diagnosis earlier on.”

Looking at Amber’s family history, these results are not surprising.

“My dad had pancreatitis in high school when he was about 16 or 17 years old,” said Amber. “His case wasn’t as severe as mine was. He underwent treatment for his pancreas once or twice, and after his gall bladder was removed, he was fine.”

With the genetic link uncovered, Giefer is hopeful that these results will also open doors to a better understanding of a disease that is affecting an increasing number of children.

“With phase two of the research taking place in the coming year, we will have the opportunity to investigate the prognosis of the disease,” said Giefer. “This will help the medical community improve the evaluation and treatment process for patients in the future.”

Living the pain-free life

Amber is no longer paralyzed by pain.

“I go to school full-time now, regularly practice Taekwondo, work out, hang out with friends, and go to football games,” said Amber. “I’m less anxious and depressed, and don’t have to worry about being in pain anymore.”

Amber is excelling in school and her favorite classes include advanced placement psychology and math.

At just 17, Amber has her career goal clearly set.

“I want to get my medical degree,” said Amber. “I hope to become a pediatrician and help kids the way Dr. Giefer has helped me. He’s an inspiration and role model to me and I hope to be at least half the doctor he is.”

Looking back on the long and arduous road of Amber’s battle with chronic pancreatitis, Louden is beyond grateful for the care her daughter continues to receive at Seattle Children’s.

“The Seattle Children’s Pancreatitis Clinic provides us with experts from different disciplines that help treat Amber,” said Louden. “Everything from nutrition to pain medicine — she has a great team.”

Amber is quick to agree, saying, “I love my team. It’s not everyday that you have the privilege to have such phenomenal doctors care for you like that.”

Far down the line, Amber now knows that when she has a child of her own, there’s a chance that he or she could suffer from the same condition she lived with.

“I know there’s a 50% chance my child will have pancreatitis,” said Amber. “But if he or she does, I will know exactly what it is when the symptoms start showing.”

Louden added, “The good part is that it won’t go undiagnosed because she’ll know what type of treatment is needed.”

This year, Amber doesn’t expect to make an emergency trip to the hospital on Thanksgiving Day.

Instead, she plans to enjoy the company of her family while gobbling up some of her favorite foods like apple pie, mashed potatoes, stuffing, and of course, a whole lot of turkey.

“It definitely hasn’t been easy,” said Amber. “But taking that leap of faith earlier this year — with careful encouragement by an outstanding doctor and exceptional medical team that only wanted the very best for me — really changed my life.”

Resources:

- Seattle Children’s Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Pancreatitis Clinic

- Therapeutic Endoscopy Program

- Research Links Genetics to Early-Onset Pancreatitis in Pediatric Patients