When Sam Foster steps onstage, guitar in hand, he lights up the room with his confident presence.

Yet behind his poised demeanor is a painful truth that begins to unravel as he lets his lyrics flow through the microphone.

Sam has battled with obsessive compulsive disorder, or OCD, most of his life.

According to the National Institute of Mental Health, OCD is a common, chronic and long-lasting disorder. It occurs when a person has uncontrollable, reoccurring thoughts, known as obsessions, and behaviors that they feel the urge to repeat over and over, known as compulsions.

In response to the social stigma that often surrounds mental health disorders, Sam initially felt ashamed of having OCD. That was, until he began expressing himself through writing music and eventually got the treatment he desperately needed.

“At first, I felt like I was harboring a shameful secret,” said Sam. “I didn’t think I could explain to people what I was going through because they wouldn’t be able to relate.”

Now at 19 years old, Sam is an accomplished musician with a catalogue of songs that narrate his journey of working to overcome his OCD and finding purpose in his struggle.

Feeling off-key

Sam’s OCD began to surface when he was in middle school.

“I was always a naturally anxious kid growing up,” said Sam. “It became apparent that my behavior was something more when I started obsessing over school.”

With his meticulousness and unrealistic strive for perfection, Sam’s parents recommended he see a mental health therapist. After evaluation, he was diagnosed with OCD and introduced to the concept of exposure and response prevention (ERP).

ERP is a therapy approach where the patient is exposed to the thoughts, images, objects or situations that cause them anxiety. They are exposed to these until their anxiety lessens.

Although Sam had the knowledge to practice ERP, he didn’t commit to doing it regularly and his condition worsened when he reached high school.

“I realized I was just trying to survive,” said Sam. “I was functioning but wasn’t enjoying anything because I was so burdened by the drive to be perfect, the need to please and about the fear of failing, which my OCD would latch onto. Every low point seemed to get lower.”

Getting in tune through treatment

Overcome with a feeling of hopelessness, Sam had hit rock bottom.

In the summer leading up to his senior year of high school, Sam’s therapist and parents suggest he try a program that could accelerate his treatment.

“I decided I’d give it a shot,” said Sam. “It ended up spurring new life into my fight against OCD.”

Sam began working with Dr. Geoffrey Wiegand from Seattle Children’s Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine team and director of the OCD Intensive Outpatient Program (IOP), to learn how to manage his OCD.

“When I met Sam, his OCD was in the high to severe range,” said Wiegand. “For patients like Sam, the program is aimed at helping children and teens ages 10 to 18 diagnosed with OCD or an anxiety disorder who have not been able to make progress in regular once weekly outpatient treatment.”

One of only a few intensive programs in the country, it offers evidence-based cognitive behavioral treatment for OCD and anxiety in both an individual and group environment. Patients participate in the program three hours per day, four days per week, and for about eight weeks depending on the severity of their OCD.

For Sam, he remained in the program for nine weeks to fully address his specific issues, one of them being ‘voice checking.’

“I had a voice checking ritual where I would do random vocalizations in response to a fear of losing my voice and not being able to sing again,” said Sam. “I would do it at least every five minutes.”

Sam was taught the exposure practice of writing scripts that would help to challenge this sort of behavior when it would surface.

“A script essentially exposes you to your most catastrophic fear,” said Sam. “One of the scripts I wrote was about losing my voice. I would read it over and over again to raise my anxiety. The more times I read the script, the more exposed to it I was, and the more my anxiety would decrease.”

Sam also worked on other behaviors that burdened him such as obsessive thoughts about finding shards of glass in his drinks, excessively practicing his guitar to reach a sense of perfection, fear of making mistakes while he was performing, feeling unintelligent, fear of failing at school, and having a negative body image.

At the beginning of every program session, the group consisting of typically six patients, would come together to each share the progress they made with their exposure practice. It was then followed by personalized sessions with a doctor, and sometimes a few other patients from the group, where they planned new exposure practice to try at home. Their parents were also taught how to help practice these activities at home with their children.

“I felt that the group dynamic was one of the most important reasons of why it was helpful,” said Sam. “There was a certain level of vulnerability that was required to open yourself up and talk about your most intense and deepest fears with people.”

As the program went on, Sam felt a sense of comfort in knowing that others truly understood what he was going through and they were there for the same purpose, working toward a common goal.

“It fostered a sense of community and encouraged us all to support one another,” said Sam.

Wiegand has witnessed many transformations in the patients who completed the program, which includes Sam.

“What they are doing is really remarkable because few people in life can say they made a list of every one of their fears and crushed each of them,” said Wiegand. “It’s an extraordinary feat that takes courage, and I’ve seen many of them become confident individuals by the time they are done with the program.”

Finding his forte

With the IOP behind him, Sam has a new sense of self confidence that has allowed him to share his lifelong passion with others.

“Music is my passion, and it’s what I love to do,” said Sam. “I was always interested in music ever since I was young. In high school, I felt the need to perform and express myself, and so I taught myself guitar and began writing songs.”

Music gave Sam a cathartic outlet.

“It was especially helpful in the moments when I was feeling really burdened and had nowhere to turn,” said Sam. “I would pick up a guitar and say what I was feeling.”

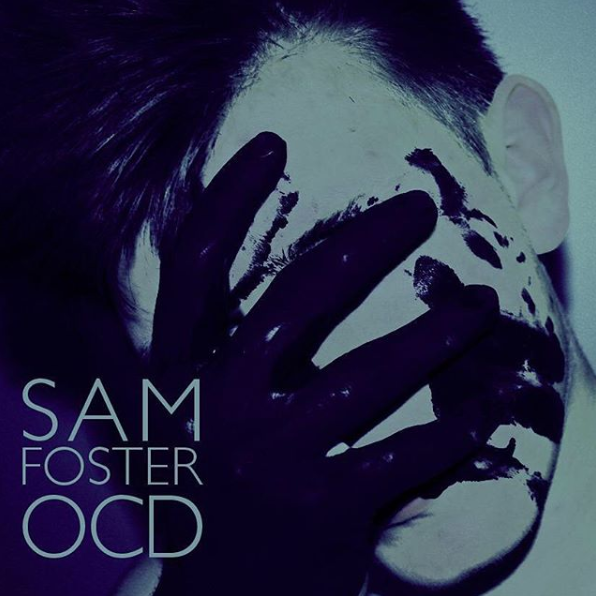

Last year, Sam’s talent for musical storytelling landed him a spot in the semifinals of MoPOP’s Sound Off! competition, which put his struggles with OCD on full display in front of a large audience. He also released his debut album aptly titled, “OCD.”

This year, he began his freshman year at the renowned Berklee College of Music in Boston.

While he’s proud of his recent accomplishments, he knows that OCD will always be something he’ll have to live with.

“Managing my OCD continues to be a struggle, especially in this point of my life when I’m experiencing a lot of change — but the struggle is nothing like it was before doing the IOP,” said Sam. “One powerful phrase that I learned in the program, which will always stick with me, is ‘do the opposite.’ By doing the opposite, it isn’t just about avoiding the ritual, it’s about aggressively going after your fear and working to overcome it.”

Seeing patients like Sam go from having severe OCD down to managing a mild level, has given Wiegand and his staff meaning to their work.

“I’m often told by my staff that working with these kids is the best part of their week,” said Wiegand. “With the program, we get to see them improve in a faster time period, which is amazing. It’s humbling to see the progress that patients like Sam make; he went from doing compulsions eight hours a day to less than half an hour a day. He’s smart, musically talented and a caring young man who has a bright future ahead of him.”

If Sam could give advice to other young people suffering from OCD, he would say not to feel ashamed of it.

“I understand how painful the struggle can be, but remember, having OCD isn’t your fault,” said Sam. “It may feel hopeless at times, but what you can do is seek treatment to get better. Don’t let OCD define you – you are you.”