It’s been 12 years, but Brandy Epling still chokes up at the traumatic memory of her firstborn’s birth.

It’s been 12 years, but Brandy Epling still chokes up at the traumatic memory of her firstborn’s birth.

It was a difficult pregnancy, with preterm labor forcing a 33-day stay at a southwest Washington hospital for the mom-to-be, followed by months of bedrest. Ultrasounds revealed the baby’s brain was a bit bigger on the left side, but the local fetal medicine doctor wasn’t overly concerned.

Induced at 38 weeks, Brandy labored for 22 hours until Emree finally emerged.

“It was probably the scariest moment of my life,” Brandy said. “When she came out, her head was grossly swollen. There was this ring of fluid around her head. Her left eye was completely enlarged and she was not breathing normally.”

It took hours to stabilize the critically ill infant, who also had fluid around her heart.

“I was not prepared for any of this because they kept telling me during my pregnancy that she was going to be fine,” Brandy said.

A family’s search for answers

The days that followed were a whirlwind of tests and scans. On day three, Emree’s seizures began — hundreds of them. The hospital staff tried numerous medications to halt them. When those failed, they told Brandy and her husband, Kevin, they were out of options.

“I told them that’s not an answer and it’s not good enough for me,” Brandy said. “They couldn’t even tell me exactly what was wrong with her.”

She began researching and found Dr. Russell Saneto, a neurologist at Seattle Children’s, the only level-4 epilepsy center in the region dedicated exclusively to pediatrics.

“I read his bio online and learned he has different ways to treat seizures other than just medicine,” she said. Brandy persuaded the NICU staff to contact Seattle Children’s and transfer the fragile 9-day-old.

“When Dr. Saneto and his team came in, they sat down and listened to us, which was not the experience we had at the other hospital,” Brandy recalled. “They said, ‘We don’t have the full picture of what’s going on with Emree right now but we’re going to figure it out.’ That’s all I wanted.”

A rare neurological condition

Tests and specialists brought an answer: Emree had hemimegaloencephaly, a rare neurological condition in which one-half of the brain is abnormally larger than the other, causing frequent seizures.

Brain surgery was too risky given how small and sick Emree was, so the 3-week-old was placed on a ketogenic diet using special formula that’s 90% fat and 10% carbohydrates and protein.

“She’s the youngest baby who had ever started it at that point. It put her body in ketosis so her brain ran off fats instead of sugars,” Brandy said. “I do believe it helped slow her seizures down, but nothing ever took them away.”

Emree was hospitalized at Seattle Children’s for four months before the Eplings could take her home. The seizures forced frequent return trips from their Winlock, Washington, home.

“The first year of her life, we were in and out of Seattle Children’s. It was like we were there more than we were home,” Brandy said.

Just shy of her first birthday, Emree’s seizures worsened and her head swelled. She was readmitted to the hospital.

“They had to intubate her and give her paralytics to help her stop seizing,” Brandy said. “At that point, that’s the only thing that stopped them.”

Epilepsy surgery at Seattle Children’s

The Eplings and their medical team decided it was time to move forward with surgery. Emree weighed only 11 pounds. The only chance of lessening the seizures and reducing the harm to her brain was a hemispherectomy, a surgical procedure that disconnects the affected half of the brain’s cortex from the other half. Seattle Children’s is one of the few centers in the world to have done this surgery more than a hundred times.

“She was still so tiny, but Kevin and I decided we had to give her a chance,” Brandy said. The next day, Emree had a nearly 12-hour surgery led by Dr. Jeff Ojemann, then-chief of the Neurosurgery Division and director of epilepsy surgery at Seattle Children’s.

Emree’s surgery went well, and the family went home 10 days later.

“It was like our daughter was born. She healed up. She learned how to suck from a bottle, how to hold her head up. She just blossomed. She was virtually seizure-free for about two years after that,” recalled Brandy.

But Emree’s seizures — about 30 a day — came roaring back.

Tests showed some tissue still firing on the left side of her brain, so the surgeons did a revision of the hemispherectomy. It helped, but the seizures persisted.

“She was regressing with all the progress that she made,” Brandy said. “She was losing all of those skills because her seizures were so bad again.”

The surgeons implanted a device called a vagus nerve stimulator to help lessen her seizures and tried many medication changes. The efforts seemed to help reduce the number and severity of Emree’s seizures.

“She was still having 10 to 15 seizures a day, but she was OK to be at home,” Brandy said. “But her regression continued — her muscle tone and voice went away, she stopped eating and drinking by mouth.”

Though her parents weren’t seeing a lot of noticeable seizures, tests revealed Emree was seizing subclinically (without symptoms) for all but one hour in a 24-hour period.

“That’s why she was losing all of her progress and basically, there was nothing more to do,” said Brandy. “So we told her care team to give us the tools to manage this at home and we’ll just enjoy her as long as we can.”

Finding hope in a clinical trial

A ray of hope came in 2019 in the form of a Seattle Children’s clinical trial. “Dr. Saneto called me and said, ‘I want Emree to be a part of a study because I really think it’s going to help her with her seizures.’ I said, ‘Whatever you want us to do, we’re in.’”

The clinical trial was based on the work of Dr. Ghayda Mirzza at Seattle Children’s Research Institute. Like many Seattle Children’s doctors, she has a dual career, both seeing patients and leading a lab team in pursuit of cures.

More than a decade ago, Mirzaa began testing brain tissue removed from kids who underwent surgery for epilepsy to see if she could find genetic changes to explain why a certain part of a brain was abnormal or caused seizures. She and her team were able to find mutations in AKT3, a gene critical for brain growth and development, that lies within an important cellular network called the mTOR pathway. Excitingly, certain medications already used for other disorders can function as mTOR inhibitors.

After making these genetic discoveries, researchers at Seattle Children’s wanted to test the effectiveness of these drugs to treat epilepsy in patients who don’t respond to standard therapies or surgery — kids like Emree.

Dr. Jason Hauptman, a pediatric neurosurgeon at Seattle Children’s, led the clinical trial using mTOR inhibitors. After meeting with him, the Eplings enrolled Emree in the study and she received her first IV of the drug.

It was nothing short of a miracle. Within a few days, her seizures stopped.

“Emree was an incredible responder to the trial medication,” Hauptman said. “She had on the order of 100 seizures a week and no surgical options for cure. Ever since we started that medication over 2 1/2 years ago, she has been seizure-free.”

Research changes a family’s life

Brandy was skeptical at first. “Before when we tried something new, there was always a honeymoon period and then everything would go back to the same,” she said. “But on this medication, she had no seizures. If she got sick, she might have a breakthrough seizure here or there, but nothing like before.

“Her physical therapist asked, ‘Do you notice Emree’s getting stronger?’ And I saw she was actually able to sit and then she slowly got her voice back. And she began chewing on teething rings, a source of stimulation for her. She started getting her smile back. You could see the joy and purpose she had before return,” Brandy said.

The team at Seattle Children’s got Emree approved for compassionate use of the study drug so her access will never be rescinded.

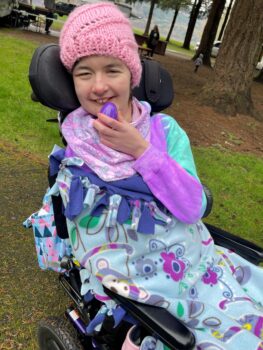

Her progress has continued. While Emree is blind and nonverbal, she babbles in what her family calls “Emree language.” She loves music, being read to by her 5-year-old sister, Kinslee, and being pushed outdoors in her wheelchair.

Once tethered to their home due to Emree’s seizures, the Eplings now embrace family outings.

“We go camping and go to the beach all the time, and it’s just amazing that she’s able to be a part of what we do as a family,” Brandy said. “She’s happy. We know that she’s not going to be like all the other kids, and that’s OK because Emree is Emree.

“Seattle Children’s has truly helped us get her to where she is today. Her doctors, on top of all the work they do seeing patients and performing surgeries, have the heart to do research to figure out a way to help these kids who have no other options.”