Summer school is in session for researchers at Seattle Children’s Research Institute, and although there are text books and a final exam, very little else about the biology course taught by Dr. Philip Morgan and his fellow scientist and wife, Dr. Margaret Sedensky, is business as usual. That’s because their students are Tibetan monks and their classroom is at a monastic university in southern India.

Summer school is in session for researchers at Seattle Children’s Research Institute, and although there are text books and a final exam, very little else about the biology course taught by Dr. Philip Morgan and his fellow scientist and wife, Dr. Margaret Sedensky, is business as usual. That’s because their students are Tibetan monks and their classroom is at a monastic university in southern India.

Modern science as truth

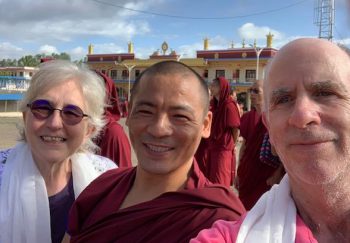

At Seattle Children’s, Morgan and Sedensky study mitochondria, which are the parts of the cells that produce energy. The two began traveling to India in 2017 as part of the Emory-Tibet Science Initiative founded by Emory University to bring faculty from western universities to teach science to the monks.

“The Dalai Lama feels that for Buddhism to grow that their understanding of the world must include all truths,” Morgan said. “He saw the need for his most serious students to learn western science, which he considers a truth, so that their religion remains relevant.”

In addition to biology, the monks receive crash courses in physics, neuroscience and philosophy. The goal of the program is for the monks to begin teaching their fellow monks and nuns once they complete the six-year curriculum.

Where compassion meets wisdom

For two weeks in June, the Seattle Children’s scientists drew on their experience as professors at the University of Washington School of Medicine to teach lessons focused on the basics of genes and cells to the monks. Anywhere from 50-100 monks attended the classes daily from 7:30 a.m. until 4 p.m. with the occasional break for chai tea.

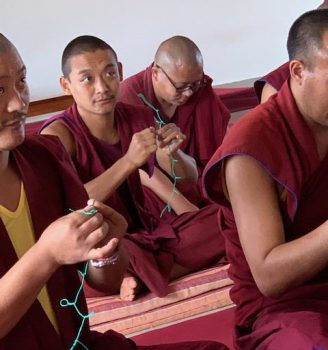

A textbook with chapters in English and Tibetan, and a translator, helped Morgan and Sedensky relay the information to their students. Hands on experiments, such as one using green wire to model how proteins fold and another employing blue decorator’s sugar, water and cooking oil to show the affinity of different substances for water or oil, further bridged the language gap between the monks and their teachers.

According to Sedensky, adaptions made on behalf of both the teachers and the students helped create a harmonious learning environment.

“Since Buddhists believe it is wrong to harm animals, any experiments that involved the dissection of insects or other animals were off limit, so we had to come up with acceptable alternatives to study cell biology like using their own cheek swabs,” she said.

On the other hand, she saw how the monks, who typically train through spirited debates, slowly warmed to the lecture-based classes.

“They needed encouragement to ask questions in class since this type of questioning is often reserved for the nightly debates they have with one another,” she said. “It took some breaking the ice, but we had students lining up with questions by the end of the session. The questions they posed revealed a profound curiosity about life.”

An enlightened return to Seattle

As with their previous trips to India, the Seattle duo say they returned to their labs in the research institute’s Center for Integrative Brain Research with new perspective.

“It has been incredibly rewarding to interact with the monks,” Morgan said. “They approach learning very differently than we do in western science. For them, it’s not important to know exactly what DNA and RNA do, but to appreciate the beauty of how things are put together.”

Morgan says his exposure to this different way of understanding has helped him see things he encounters in his works for their real importance. He saw how the monks brought openness and compassion to their study, and he now looks for ways to incorporate those values into his work.

Their time at the monastery left Sedensky with a similar impression.

“I find their ability to focus on the big picture so refreshing,” she said. “They asked big questions like ‘Where did the first cell come from?’ that made us think beyond the information you would find in a textbook. Sometimes we were stumped, but I enjoyed searching for the answers.”