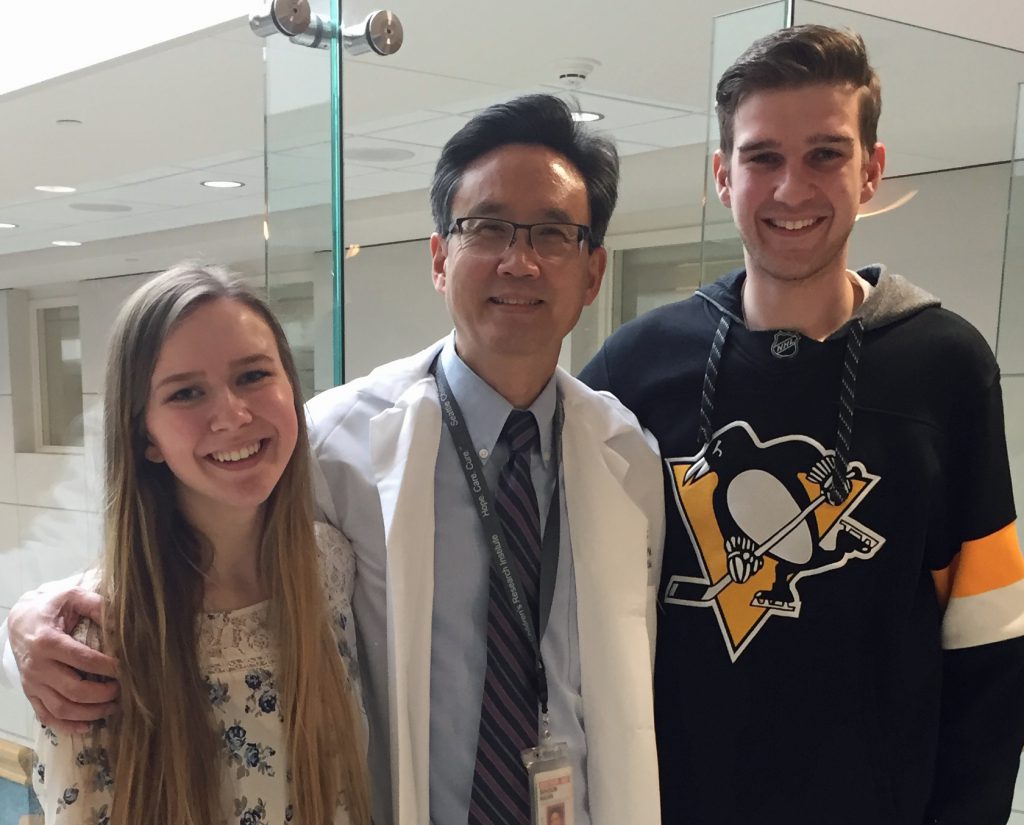

The lifetime goal of Dr. Sihoun Hahn, director of the Wilson Disease Center of Excellence and investigator in Seattle Children’s Research Institute’s Center for Integrative Brain Research, is one step closer to being achieved.

After more than 30 years studying Wilson disease, Hahn’s newborn screening test for this rare genetic condition will be trialed in a pilot study by the Washington State Department of Health by the end of the year. If the study is successful, Hahn’s test could soon be used to diagnose infants across the country with this life-threatening, but easily treated, disease.

Wilson disease is a genetic disorder that causes excessive copper to accumulate in the body. Although the copper accumulation begins at birth, symptoms do not appear until late childhood or early adolescence. By that time, patients often have serious, permanent effects, including liver failure or neurological deterioration.

Additionally, one-third of people with Wilson disease experience psychiatric symptoms, such as abrupt personality changes and inappropriate behavior, depression, neurosis or psychosis.

Susan Miller’s daughter, Julia, was diagnosed with Wilson disease by chance when she was 6 years old. She’d been sick more than usual, so her pediatrician ordered a routine blood test that showed unusually high liver enzymes. A subsequent biopsy at Seattle Children’s revealed scar tissue in Julia’s liver, which led to a diagnosis of Wilson disease.

Julia is now 21 years old. Because her illness was detected early, she’s been able to live a healthy life with simple, daily treatments of zinc.

Not all patients are so lucky. Ryan Wyckoff, of Wasilla, Alaska, was 15 years old when he became seriously ill for the first time in his life. He was lethargic and had a high, uncontrollable fever. He gained 15 pounds over two days caused by fluid filling his abdomen.

“It’s terrifying to have something seriously wrong with your son that no one can figure out,” said Ryan’s mom, Lisa. “We felt so helpless.”

An MRI revealed Ryan had advanced, life-threatening scarring in his liver. He was flown to Seattle Children’s by medevac and later diagnosed with Wilson disease.

Decades spent searching

Hahn began caring for patients with Wilson disease as a fellow at the National Institutes of Health in 1990. While the disease is rare — affecting around 150 newborns in the United States each year — the patients Hahn treated left a lasting impression on him.

“It was very sad,” Hahn said. “These children seemed perfectly healthy and then suddenly they rapidly deteriorated. Many had permanent brain damage or needed liver transplants. Some had tremors, slurred speech, or could not walk or swallow.”

Hahn began studying the molecular biology of Wilson disease and discovered the disorder was caused by a genetic defect in the ATP7B gene. While this led to a better understanding of the disease, patients still weren’t being diagnosed until after they developed significant effects.

Hahn realized the best way to help children with Wilson disease was to detect it early. That’s when he began focusing his research on developing a newborn screening.

Over 20 years, Hahn searched for a gene or protein that could be used to reliably identify Wilson disease. He first developed a test that identified ceruloplasmin, a protein made in the liver that carries copper to the bloodstream. But after screening thousands of newborn babies, Hahn realized the test resulted in too many false-positive results.

“To be a leader in a field, you have to continue looking forward. That is Dr. Hahn. He has a vision of how this exciting work will be valuable for his patients and their families for future generations. I am very excited to see how his test performs.”

— Dr. Michael Schilsky, chair of the Wilson Disease Association Medical Advisory Committee, occasionally collaborated with Sihoun during his years of research.

Still, Hahn persevered.

“I didn’t want to give up,” Hahn said. “It was my life’s mission. I was lucky to have support from Seattle Children’s Research Institute and the NIH so I could keep going.”

Hahn knew Wilson disease was caused by mutations in the ATP7B gene, so his team developed a method of measuring ATP7B in dried blood spots from newborn babies’ heel pricks.

The ATP7B screening test proved to be accurate, but Hahn needed to build commercial test kits before it could be trialed. With community support, Hahn created a startup company to build testing kits that will be used by Washington state’s newborn screening laboratory in a pilot study that will be launched later this year.

Hahn expects the study will lead to Food and Drug Administration approval, after which he will apply for the Wilson disease screening test to be included in the nationally recommended newborn screening panel so that infants across the country would be tested before symptoms appear.

If approved, Hahn’s screening method could also be used to diagnose at least three other primary immunodeficiencies that newborns are not currently tested for — X-linked agammaglobulinemia, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome and Adenosine deaminase deficiency.

“If diagnosed early, each of these conditions can all be effectively treated and children can go on to live normal, healthy lives,” Hahn said.

In support of research

Lisa knows how significant early detection is. Although Ryan was diagnosed less than 48 hours after arriving at Children’s, he already had permanent damage to his liver. He quickly started treatment of Syprine — a chelating agent that removes copper from the body. Years later, Ryan’s cirrhosis caused his spleen to swell, requiring emergent, life-threatening surgery to remove it.

“Working with Dr. Hahn has been like watching light shine through rain clouds. He’s so committed to making this a livable disease; it gives us hope.”

— Susan Miller, mother of Julia

“Ryan wouldn’t have sustained so much damage to his organs if we had found out about his disease sooner,” Lisa said. “I think about every time he ate high-copper foods like chocolate or a peanut butter sandwich. Those things were terrible for him, but we had no idea.”

Both Ryan and Julia, as well as their asymptomatic siblings who also tested positive for Wilson disease, have contributed blood samples to Hahn’s research.

“I understand Wilson disease is rare,” Lisa said. “But if a newborn screening could prevent just one kid from having to deal with the trauma my son has faced, then we will do anything we can to help.”

After 30 years, Hahn’s dedication to this research has only grown. “I would like to retire soon,” he said. “But not until we have a national screening for Wilson disease.”