On a Saturday in March, 13-year-old Trey Lauren was playing with his friends at a birthday party when he fell and cut his knee on a nail. It was a typical injury for a kid his age, but what resulted was anything but typical.

On a Saturday in March, 13-year-old Trey Lauren was playing with his friends at a birthday party when he fell and cut his knee on a nail. It was a typical injury for a kid his age, but what resulted was anything but typical.

Trey was taken to a local emergency room that night, and by Sunday morning his wound had been closed with six stitches. But when Monday morning came, he was too sick with a fever to go to school, and his knee had begun to swell. Trey’s parents, Mark and Randi Lauren, decided to take him to urgent care, where his stitches were removed and he was started on antibiotics. However, later that night, Trey’s fever persisted, and the swelling in his knee had only gotten worse.

One trip to the emergency room later, Trey received an additional dose of broad spectrum antibiotics, and the decision was made to transfer him to Seattle Children’s Hospital.

Due to the severity of Trey’s symptoms, he was quickly examined by Seattle Children’s Orthopedic Surgeon, Dr. Klane White. “I went to see Trey, and it just didn’t seem right to me,” said White. “It became increasingly clear that this was not a run of the mill infection, and with the suspicion that this could be Necrotizing Fasciitis, we needed to act quickly.”

Necrotizing fasciitis, better known as flesh-eating bacteria, is a serious infection that spreads rapidly and destroys the body’s soft tissue. It’s extremely rare, “like being struck by lightning,” said Dr. Richard Hopper, chief of Plastic Surgery at Seattle Children’s, who was part of Trey’s medical team. It can claim a limb – even a life – if not neutralized very quickly.

A unique protocol

Doctors at Seattle Children’s, one of the few providers in the region capable of treating necrotizing fasciitis in children, see a disproportionate amount of cases and have developed a unique protocol for treating it.

“The main problem that arises when dealing with necrotizing fasciitis is that the symptoms of the disease are not always cut and dry, and can often be quite subtle,” said Dr. John Waldhausen, division chief of Pediatric Surgery at Seattle Children’s. “The only way to confirm the diagnosis is by opening up the infected area in surgery, so we needed to come up with a way to make this decision quickly.”

Waldhausen, working with surgeons from the Seattle Children’s Orthopedic, Pediatric and Plastic Surgery divisions, developed a unique protocol for treating necrotizing fasciitis that requires collaboration between the three specialties as soon as a suspected case is identified. In these cases the group comes together to examine the patient and mutually decides upon the proper course of treatment.

“Our protocol requires us to be fairly aggressive in our surgical approach, as this disease is a lot like a forest fire beneath the skin,” said Hopper. “You can’t just put out the fire. You have to get ahead of it to stop it from spreading.”

The swift collaboration made all the difference for Trey, whom the group decided needed emergency surgery. Surgery confirmed the diagnosis, and revealed that the bacterium was spreading rapidly.

“This is where the collaboration between specialties really pays dividends,” said Dr. Patrick Javid, an attending surgeon in the division of Pediatric Surgery. “Often this infection will begin in one place, but it will spread to a joint or the torso, so it helps to have both orthopedic as well as plastic surgery involved. The primary objective is to stop the spread of the infection, but since plastic surgery handles the reconstruction later, their expertise is invaluable in guiding the approach so that we can preserve the most long-term functionality for the patient.”

The road to recovery

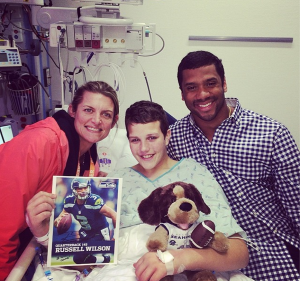

Trey went through 13 surgeries in 23 days before his leg was finally free of bacteria, but he never lost his fighting spirit. Even when he and his family had more questions than answers, his family said he was the most positive person in the room. Trey was moved out of the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU) on March 31 and finally got to go home on April 9.

Trey’s goal was always to get back to being the active kid he was before his injury and for him that meant getting back to playing baseball. Recently, nearly two months to the day since his first surgery, he played in his first baseball game. Several days later he got his first hit, a double.

His family is grateful to the medical team at Seattle Children’s for not only saving Trey’s life, but also helping him get back to being a regular 13-year-old.

“We were confident that we could beat this,” said mom Randi Lauren. “But Trey’s amazing doctors and nurses, and the outpouring of support we received from our community helped us maintain that outlook when times got tough.”

“I always knew I had a big family,” said Trey. “But I never knew how large my family really was.”

Resources:

- Seattle Children’s Division of Pediatric Surgery

- Division of Orthopedics and Sports Medicine

- Division of Plastic Surgery

- Tips for Preventing Bacterial Infections