Earlier this year, Nicole D’Ambrosio found herself in front of a room full of scientists that were gathered in part to discuss their progress on a novel cell therapy that has the potential to one day save her son’s life.

She had been asked to present her family’s story as part of a company-wide meeting at Casebia Therapeutics in Boston. As she began, she recounted how her only child, 7-year-old Sonny, has reached the brink of death more times than she can remember because of the rare autoimmune disorder he was diagnosed with as an infant. How the bone marrow transplant he received was the only thing that could save him, but caused endless complications, including skin necrosis and epilepsy.

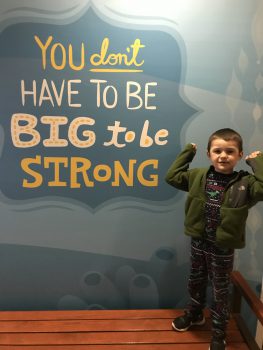

How the thought of going through another transplant when the initial transplant failed compelled her and her husband to pack up their home and move 3,000 miles west to seek other options. How she lies awake at night praying that Sonny’s body can stay strong enough until a safer treatment comes along. How, despite everything he’s been through, Sonny is still a happy little boy with a wicked sense of humor.

When she finished, there wasn’t a dry eye in the room. Person after person came up to her afterward, thanking her for sharing her story. Several explained how their research to develop a new way to target Sonny’s disease as part of a joint effort between Seattle Children’s Research Institute and Casebia had new meaning after hearing her story. They were dedicated to helping Sonny and other children like him. D’Ambrosio left similarly inspired.

“This therapy they are working so hard to get into a clinical trial would be life-changing for us and so many others,” she said. “These scientists are giving my child a future. They’re giving us hope that we didn’t have. I can’t think of how to thank someone for that. There are no words.”

The ultimate autoimmune disease

After Sonny developed constant diarrhea and vomiting starting at 4 months old, D’Ambrosio and her husband Anthony found themselves desperately seeking answers at a hospital near their home in Scituate, Massachusetts.

“Our once chubby beautiful boy was nothing but skin and bones fighting to live,” D’Ambrosio said. “He was tested for everything imaginable. They still had no idea what was happening.”

The D’Ambrosios spent nearly a month in the hospital before doctors diagnosed Sonny with an autoimmune condition called immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked syndrome (IPEX).

A genetic condition that primarily affects males, IPEX occurs in an estimated one in 1.6 million people. The disease left Sonny without a type of white blood cells known as regulatory T cells. Without these cells that help regulate healthy immune responses, other types of Sonny’s T cells attacked his major organs, including his skin, gut, heart and kidneys.

“These children have the ultimate autoimmune disease,” D’Ambrosio said. “It’s not just one thing that goes wrong; everything goes wrong.”

Seeking a safer option

Currently, the standard treatment for IPEX is a bone marrow transplant from a compatible donor. Even when a donor is available, children with IPEX may be too sick to undergo transplant because the risk of complications is high. Without a transplant, many children with IPEX do not survive past their second birthday.

At the urging of his doctors, Sonny underwent transplant as soon as they found a compatible donor. Complications arose even as doctors prepared Sonny for the transplant and continued for the next 15 months.

“Anything that could have gone wrong with Sonny, went wrong,” D’Ambrosio said. “Our amazing boy somehow always beat the odds. Today, he’s a walking side effect of transplant, but we walked away with his life.”

Though Sonny, then 2, was finally thriving, his parents soon learned that he no longer had any of the donor cells from his transplant. His doctors pushed the family to move forward with a second transplant, fearing his IPEX would return.

“We knew in our hearts a second transplant would kill him,” D’Ambrosio said. “We needed an option safer than transplant, and so we decided to move our family and Sonny’s care to Seattle.”

Sonny meets leading IPEX specialist

In Seattle, they established care with Dr. Troy Torgerson, an immunologist at Seattle Children’s who specializes in treating children with IPEX. Torgerson has followed more children with IPEX than any other clinician in the world.

“After one visit with him, we knew he was who we should have been working with all along,” D’Ambrosio said. “He truly understands how different each IPEX case is. We finally found someone who wanted to treat Sonny, not just IPEX.”

Torgerson shared the opinion that a second transplant would be highly risky for Sonny and thought it best to focus on getting him stronger. Knowing the IPEX symptoms would return and progressively get worse again, Torgerson wanted Sonny at full strength when that time came.

“IPEX is a difficult disease from the standpoint that without a definitive therapy like a bone marrow transplant, patients accumulate more and more autoimmune problems because every time their immune system gets revved up, it can’t turn off,” he said. “It’s like the radio volume gets dialed up higher and higher and never gets turned down. Our goal is to keep Sonny’s IPEX quiet for as long as possible.”

According to Torgerson, this strategy also allowed time for any new options to become available through clinical trials.

“If an alternative to transplant reached the clinic and could potentially offer Sonny a better chance of surviving, we all agreed it was worth holding out for,” he said.

Cell therapy targets IPEX in lab studies

In addition to his clinical practice, Torgerson leads research to develop new therapies for IPEX from a lab at Seattle Children’s Research Institute. Torgerson and other researchers in the Center for Immunity and Immunotherapies, including center director Dr. David Rawlings and Dr. Andy Scharenberg, now the Chief Scientific Officer at Casebia, provided the initial proof of concept studies for the therapy that excited D’Ambrosio at the meeting in Boston.

The novel approach they developed uses gene editing to transform the T cells that promote autoimmunity into cells that function like regulatory T cells. The hope is that the resulting regulatory-like T cells will treat conditions like IPEX by quieting the overactive immune response.

“The idea is that we will engineer a patient’s own immune cells to fight their disease,” Torgerson said. “When infused into the patient, these edited T cells will suppress the immune system, controlling their disease.”

To do this, scientists targeted the FOXP3 gene, which produces a protein needed for regulatory T cells to develop and function normally. Mutations in FOXP3 prevent the gene from making this protein in children with IPEX. By inserting a correct version of the FOXP3 gene and forcing its expression in the T cells, the cells could then develop into regulatory-like T cells. This approach has the potential to help those with IPEX stay in remission for longer with less need for immune suppressing drugs, which carry both significant risks and side effects.

Since launching the research collaboration with Casebia in 2017, the joint team has successfully applied in the laboratory the gene editing technology CRISPR/Cas9 to their approach. The support from biotech coupled with the relative ease with which CRISPR/Cas9 can make the genetic changes to the T cells is accelerating the pace of their discoveries in the lab.

Research shared at the 2019 American Society for Gene and Cell Therapy annual meeting by Dr. Yuchi Honaker, a research scientist supervisor in the Rawlings lab, demonstrated how this approach effectively suppressed IPEX symptoms in lab models. The teams are now working on preclinical work to potentially launch a clinical trial at Seattle Children’s.

“For patients with a rare disease like IPEX and with limited treatment options, this is exciting progress,” Torgerson said. “Even more importantly, what we learn from developing this approach for IPEX may help us in treating more common diseases like graft versus host disease in organ transplant, rheumatoid arthritis and lupus.”

The need for a safer treatment

Under Torgerson’s care, Sonny remained IPEX symptom-free for five years before his skin began to flare up. Then came the relentless stomach pain.

“By the end of last year, every symptom had returned,” D’Ambrosio said. “The months that followed proved extremely difficult for Sonny.”

Sonny’s symptoms persisted, causing him to miss most of kindergarten. Having since moved back to Massachusetts to be closer to family, Sonny’s doctors at home work closely with Torgerson on a treatment plan, which includes immune suppression drugs.

Together, they got his symptoms under control so that he could attend first grade regularly this year. Sonny even felt well enough to travel with his parents to San Diego in May to meet another family they connected with through the online group D’Ambrosio helped start for families of children with IPEX.

“We are so thankful to meet the children we follow online and watched struggle to survive, seeing them running and playing with our Sonny, enjoying an ice cream, and overall just having the chance to be kids,” she said.

She cherishes those moments as each day brings new challenges for Sonny. She hopes new options, like the cell therapy in development, are available to Sonny through a clinical trial before a second transplant becomes their last resort.

“To know your child could lose their life or suffer a lifetime of complications from the very treatment that is supposed to help them is heartbreaking and leaves many of us in limbo, afraid to transplant or re-transplant our children,” she said. “Like us, so many families are holding out hope that a safer treatment or cure for this terrible disease will be available soon.”

Even though she doesn’t know what tomorrow might hold for Sonny, D’Ambrosio says they still count themselves among the lucky ones.

“Our son is here, and he is happy even with everything he has to go through,” she said. “It is a hectic life full of stress and constant worry, but it is also such a beautiful one full of hope for a cure and for a future.”

Resources

- Seattle Children’s Program in Cell and Gene Therapy

- Immunotherapy Gene Editing Advances Extend to Type 1 Diabetes