Donna West remembers her daughter, Emma, being born with a mark on her face. Part of her right cheek was raised and dark purple, like a bruise. A dermatologist diagnosed the mark as a benign extravascular hemangioma, a term that is no longer used, and said not to be concerned. A hemangioma is a collection of extra blood vessels in the skin.

However, as years passed, the hemangioma grew larger and began to hurt. When Emma, now 11, would hang upside down in the playground, it would throb. If she coughed, the mark would get inflamed and shiny.

“When she would have a coughing spell from her asthma or a cold, the pain was like clockwork,” West said. “We were told it could go away, but that wasn’t happening.”

Until receiving care from Dr. Jonathan Perkins, clinic chief of vascular anomalies at Seattle Children’s, who performed surgery on Emma with the help of a new technique called facial nerve mapping, the family didn’t have an accurate diagnosis for the hemangioma or knowledge of treatment options.

“We didn’t even know that a Vascular Anomalies program existed,” West said. “Nobody had talked to us about it.”

A sense of relief

Growing up, West would tell Emma that her hemangioma made her unique.

“I told her, ‘I know it’s hard, people will say things, but we’ll try to teach them instead of getting angry,’” West said. “We made friends with people who were curious and wanted to know what was on her face.”

However, sometimes the family would get strange looks, or people would stop talking to them when they saw Emma’s mark. Strangers and classmates would frequently approach Emma and ask questions.

“It got a little frustrating because my friends would ask a lot about it, and it was annoying having to repeat it again and again,” Emma said. “But it was nice to have something that other people don’t have at my school.”

Emma continued to have pain, whether she was at the park, playing soccer or watching a play. When Emma was 8, West learned about Seattle Children’s Vascular Anomalies Clinic program while she was working for someone who had recently donated to the Vascular Anomalies program.

“There’s a reason you cross paths with people,” West said. “When we learned about Dr. Perkins, it was a real blessing.”

Perkins remembers Emma being withdrawn at first.

“When they came to see me, Emma made zero eye contact, largely because of this hemangioma on the side of her face,” Perkins said. “It really affected her development.”

Through a CT scan, Perkins found that Emma didn’t have an extravascular hemangioma that would become smaller with time, but rather a non-involuting congenital hemangioma (NICH), which does not shrink. The new diagnosis reflected how Emma’s hemangioma increased in size as she grew up and did not disappear with time. West said Emma’s correct diagnosis was important to know to move forward with the correct treatment. Emma saw the mass of blood vessels in her hemangioma and how it connected to the facial artery.

“With new information about these vascular lesions, we can come to different diagnoses and find effective treatments,” Perkins said. “Emma illustrates how people have previously been told, ‘This will go away and get better,’ and it doesn’t. If the family had the correct diagnosis initially, Emma would have likely received different treatment for her NICH.”

Differentiating infantile hemangiomas from NICHs is important for determining treatment. A blood pressure medicine called propranolol shrinks infantile hemangiomas but does not work to shrink NICHs. No medical treatment is available for these lesions, but surgery is an option. Although hesitant at first, the family decided to have the operation due to Emma’s discomfort and after meeting her care team.

“The care at Seattle Children’s was wonderful,” West said. “We just felt a sense of relief, and we felt more knowledgeable after talking with the staff.”

Technique leads to safer surgeries

Surgeries to remove facial vascular anomalies can be challenging. The small and intricate facial nerve typically comes out from the skull below the ear canal and fans out across the face in five branches. The branches are 1-2 millimeters in diameter, making them hard to see during a surgery. Another difficulty is distorted nerve branches due to the vascular anomaly.

“It’s all about preserving the nerve function to avoid causing lifelong problems,” said Dr. Randall Bly, a pediatric otolaryngologist at Seattle Children’s. “If the facial nerve is injured, that can have a serious impact on the patient, such as being unable to smile, raise an eyebrow or close their eyes. It could affect how they communicate and convey emotion. We read people’s faces all the time.”

Perkins told Emma and her mother that a new facial nerve mapping technique would have almost no risk of nerve injury and minimal scarring. The technique involves Seattle Children’s neurophysiology team helping surgeons identify the location of the facial nerve. Before surgery, neurophysiologists use electromyography to stimulate facial nerve branches and determine their location. Surgeons can then accurately draw the nerve’s position on the patient’s face with a marker. Neurophysiologists continue to monitor nerve activity during the procedure and help guide surgeons by providing real-time feedback.

In a study published earlier this year, Bly and Perkins found that pre-operative facial nerve mapping significantly reduced short and long-term facial nerve injury rates when removing facial vascular malformations. Two years after surgery, researchers found facial nerve weakness was 2% in cases when facial nerve mapping was performed, compared to 19% when nerve integrity monitoring, the current standard of care, was used. Facial nerve mapping has also led to shorter surgeries and smaller, fewer incisions, and makes it possible to remove malformations where surgery was not recommended due to the risk of nerve injury.

“The most important thing for me is to be able to tell a child’s family that this technique makes the nerve injury risk almost zero,” Bly said. “Now, we take an entirely different surgical approach and are able to offer treatment to more patients who want to remove an anomaly that is causing functional problems or is disfiguring.”

Bly and Perkins said facial nerve mapping has improved their practice so much that they wouldn’t attempt surgeries on facial regions without it. Seattle Children’s is one of the few pediatric hospitals in the country that uses this technique. Since it was adopted in 2005, Seattle Children’s has performed nearly 100 procedures with facial nerve monitoring.

“The shortening of the operating room time by 79 minutes and an extremely low risk of facial nerve injury is a huge deal,” Perkins said. “In conventional nerve monitoring, patients are usually left with facial nerve weakness. One of our jobs is to reassure people. I can now let families know about facial nerve mapping and they feel much better going into surgery.”

Reaching her full potential

Emma had surgery in August 2016. With the help of neurophysiologists, Perkins saw Emma’s facial nerve splayed out around the lesion. After mapping the nerve, he removed Emma’s lesion directly with a small incision. Emma’s recovery took only a few days and she removed her bandage after a month.

She was able to go on a birthday trip to California and attend her back-to-school orientation with no issues.

“Everything went so smoothly,” West said. “Everyone commented on what a great job Dr. Perkins did and how strong Emma was.”

After the surgery, the family asked to see photos of the nerve mapping.

“It’s so critical that they have the technology they used for Emma’s surgery for us to have the great outcome we had,” West said.

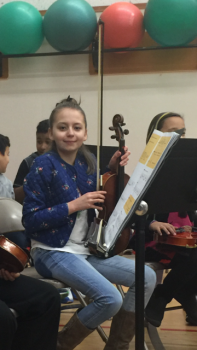

Since the surgery, Emma has started playing soccer again and has performed in two talent shows, singing and playing her ukulele. She no longer worries about pain.

“It’s remarkable to see,” West said. “Emma says her confidence has just soared since the surgery. Before, she would barely speak because she was so shy. She has really opened up and can run around like other kids. Her music teacher has even commented on how she engages in class more and shows interest in different instruments. Overall, we’re pretty ecstatic.”

As for her care team, they’re pleased to see Emma is now able to enjoy her life to the fullest.

“We want our patients to be able to reach their full potential,” Perkins said. “It’s rewarding to see patients like Emma be able to confidently go into middle school or do the activities they love without the worry of their hemangioma.”