When other kids ask Reid Watkins, 8, about the leg braces he wears, he likes to tell them they help him ‘walk awesome.’

When other kids ask Reid Watkins, 8, about the leg braces he wears, he likes to tell them they help him ‘walk awesome.’

The outgoing third grader was diagnosed with cerebral palsy and hydrocephalus at 16 months old. Until undergoing two surgeries over the course of two years at Seattle Children’s, both conditions had limited his ability to walk on his own.

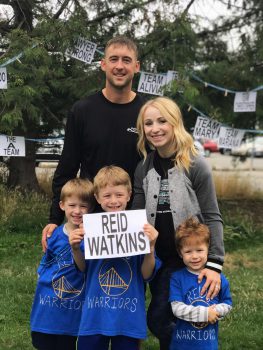

That made taking part in this year’s Hydrocephalus Association Seattle WALK to End Hydrocephalus all the more important to Reid. For the last seven years, the Watkins family has participated in the walk at Magnuson Park as a way to raise awareness about the condition.

Before his surgeries, Reid completed the walk with the assistance of a stroller or his parents. After walking the whole distance last August, Reid toed this year’s starting line ready to race. For the first time, he planned to run some of the 1.5 mile walk with his younger brothers Cohen, 6, and Jensen, 3.

“I just want to run fast,” Reid said.

Life-altering condition leads to multiple surgeries

Hydrocephalus is a life-altering, life-threatening condition caused by an abnormal accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), resulting in pressure on the brain. The most common treatment for hydrocephalus is brain surgery to implant a medical device called a shunt. Shunts effectively drain excess CSF from the brain, but often have complications that can require multiple brain surgeries over a patient’s lifetime.

Before he celebrated his fourth birthday, Reid already had three brain surgeries to place and then repair his shunt twice. He also received weekly Botox injections and therapies to help manage the spasticity, or high muscle tone, in his legs caused by cerebral palsy.

His parents ultimately decided to move Reid’s care to Seattle Children’s when he was 4.

“We weren’t seeing great results,” said his mother, Kaitlin Watkins. “It came down to wanting more treatment options beyond what they could offer us.”

Seattle Children’s program offers new treatment options

Since making the switch, Reid has had most of his care managed through Seattle Children’s Tone Management Program. His first surgery called single-event multilevel surgery (SEMLS) was performed in 2016 by Dr. Suzanne Yandow, an orthopedic surgeon and chief of Seattle Children’s Orthopedics and Sports Medicine Department. This surgery is used to correct bone and soft tissue problems in the lower extremities, allowing for more balanced muscle and joint function.

“After his SEMLS surgery, last year was the first time Reid was able to do the walk on his own,” Watkins said. “It really helped him use the back of his heels more rather than being up on his toes, giving him the ability to walk a little bit further more independently.”

With the great results from the SEMLS surgery, the Watkins turned to a neurosurgery called selective dorsal rhizotomy (SDR) to provide further relief by relaxing the muscles in his legs so that he could walk longer distances without fatiguing as quickly.

“SDR addresses the underlying cause of a child’s spasticity and can decrease the need for future orthopedic surgeries because it reduces the muscle tone permanently,” said Dr. Samuel Browd, the neurosurgeon in Seattle Children’s Neurosciences Center who performed Reid’s SDR this past November. “Even for children with mild muscle tone like Reid, the results can be transformative.”

A step forward

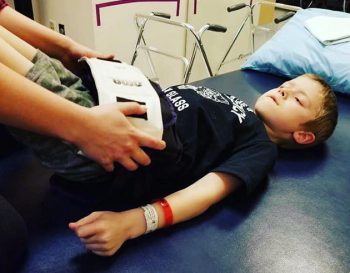

Reid spent three weeks in the hospital after his SDR, relearning how to use the muscles in his back and his legs through rehabilitation. Seattle Children’s is the only hospital in the Pacific Northwest with the expertise to offer SDR and comprehensive inpatient rehabilitation.

Reid worked hard to gain strength and steadiness during the three hours of daily therapy.

“At first it was really hard to see him go through the surgery because he really had to take a step back before he could take a step forward,” Watkins said, “but by 10 days post-op, Reid was crushing goals most kids don’t meet until after they go home. We were so proud of him.”

Reid shares his message of hope for others with hydrocephalus

Through outpatient therapy at Seattle Children’s South Clinic near the Watkins’ home in Auburn, Reid continues to make huge strides. Because he’s stronger, more stable and has better range of motion, he can do things that weren’t possible before SDR like join his friends outside at recess and run the bases for his little league team.

“He’s super social, so it’s important to him to be with his peers and feel like he’s a part of things,” Watkins said.

Since Reid’s condition has impacted their lives in every way imaginable, the Watkins say they have been lucky to find support in the Seattle hydrocephalus community. In addition to showing off his new speed, the walk organizers invited Reid to kick-off this year’s walk by sharing his story with event attendees.

When it was his turn to speak, Reid proudly told his supporters made up of his family, friends, other walkers and many from the neurosurgical team at Seattle Children’s, “Sometimes I feel like people don’t see me for who I am but only for what I can’t do. I want people to see me as Reid, a pretty rad 8-year-old with big plans to change the world.”

Off to the races

And with a quick snip of the starting line tape, Reid was off to the races.

“It’s incredible when you think about how a surgery can have such a profound impact on a kid like Reid’s life,” Browd said as he watched Reid and his family start the walk. “It gives kids with spasticity the opportunity to do the things that are innate to every kid, like running and playing. They can socially engage in ways that weren’t possible before.”

As Reid approached the finish line running, Watkins took out her phone wanting to be sure to get a video of the moment.

“It’s just so cool to see him own this; my mama heart is so full right now,” she said. “When we first learned of Reid’s diagnosis, we assumed it meant his life would follow a certain path. Now, as we’ve discovered new options, we’re all about pushing the limits so that Reid can have the life he wants. We let that drive us instead of focusing on what he can and can’t do.”

Resources

- Selective Dorsal Rhizotomy at Seattle Children’s

- Hydrocephalus Association

- Surgery and Rehab Help Arabelle Lasso Life in Junior Rodeos

- Follow Dr. Browd on Twitter