April Merrill is a 6-year-old who loves to sing and dance. Yet, her struggle with an anxiety disorder called selective mutism hinders her ability to do the activities that showcase her vibrant and joyful personality.

April Merrill is a 6-year-old who loves to sing and dance. Yet, her struggle with an anxiety disorder called selective mutism hinders her ability to do the activities that showcase her vibrant and joyful personality.

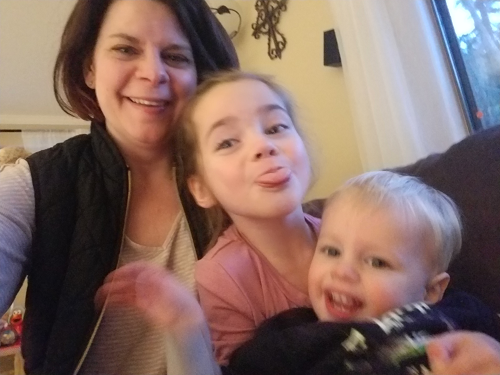

“Her voice disappears, as April describes it,” said Kelly Merrill, April’s mother. “She said that she wants to talk but can’t seem to find her voice.”

As April was growing up, Merrill noticed signs in her daughter that indicated something might be wrong.

“When April started to talk, she could only verbalize 20 or so words,” said Merrill. “She was 2 years old at the time and I noticed she couldn’t expand her vocabulary.”

A year later, April’s vocabulary did increase slightly, and speech therapy evaluations indicated interventions weren’t required. However, with April in daycare, Merrill thought the exposure to other kids and teachers might eventually help her daughter to develop her communication skills.

“She was always shy and it took a long time for her to warm up to people,” said Merrill. “When there were changes that occurred at daycare, such as a teacher change, she had issues adjusting. It would take her a couple of weeks to get comfortable and start talking to that person.”

The year before April started kindergarten, Merrill noticed that her daughter’s lack of speech extended well beyond social anxiety.

It became most evident when April and her family moved into a new home with her grandparents.

“Before her grandparents moved in, she was fine talking to them whenever they visited,” said Merrill. “Then, when they began living with us, she stopped talking to them altogether.”

Inability to speak reaches its peak

The signs April displayed are common to most children with selective mutism.

The signs April displayed are common to most children with selective mutism.

Dr. Kendra Read, an attending psychologist and director of anxiety programs at Seattle Children’s who works with patients with selective mutism, has seen symptoms of the disorder vary from child to child, however she knows that certain symptoms are universal within this population of children.

“Most children with selective mutism are verbal and even outgoing at home, but completely or mostly nonverbal at school or around strangers outside of the family,” said Read. “It’s almost like they become ‘paralyzed’ with fear or seem to ‘shut down’ when they are unable to speak.”

In April’s case, her disorder overcame her at times and even consumed her ability to speak to her own mother in particular situations.

“If I visited her at daycare, she wouldn’t speak to anybody – even me,” said Merrill. “But if I wasn’t there, she would go on speaking to her classmates and teachers and everything was fine.”

When April entered kindergarten, she didn’t speak to anyone.

Her teacher noticed her behavior and thought it could be selective mutism.

“April’s teacher was familiar with selective mutism because there was another student she had who was diagnosed with it,” said Merrill.

The teacher recommended that Merrill call April’s doctor who then referred April to Seattle Children’s for evaluation.

“At her first appointment at Seattle Children’s Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine clinic, we met with speech-language pathologist Brenda Ray,” said Merrill. “She was so wonderful to work with. She made working with April look so easy, getting her to open up, at least non-verbally, as she was still hesitant to speak at the time. However, I could tell it made her feel more comfortable, and that we were in the right place to begin treatment.”

In January 2018, Merrill and April embarked on an 8-week group program that would help transform April’s ability to communicate.

A new program provides hope

With the help of her team, including speech-pathologist Brenda Ray and mental health therapist Marcy Couckuyt, Read created the Selective Mutism Group at Seattle Children’s in April 2017.

With the help of her team, including speech-pathologist Brenda Ray and mental health therapist Marcy Couckuyt, Read created the Selective Mutism Group at Seattle Children’s in April 2017.

“We serve two age groups; one for young children and the other for ‘tweens,’” said Read. “It is an 8-week program and each session is 90 minutes long allowing for children and their parents to absorb as much information and skills as possible in helping to treat the disorder.”

The first session serves as an introduction to the group and involves only parents. They are taught about the foundation of selective mutism, general information about the disorder and ways to help treat it.

“During the first session, I was not only grateful for what I learned, but I also felt comfort in knowing that I wasn’t the only parent dealing with the challenges that come with selective mutism,” said Merrill.

Kids join their parents for the seven remaining sessions that typically start with a game or icebreaker to get the kids comfortable and encourage them to use their verbal skills.

“After a short warm-up exercise, the kids and parents would break into separate groups,” said Merrill. “The kids would spend their time working on various arts and crafts projects to help them develop their communication skills.”

An exercise that April learned from the sessions that Merrill says she still uses today is a temperature chart that helps identify the level of difficulty she has in speaking at a certain time.

Breaking the silence

A major breakthrough happened in the fourth session that April attended.

A major breakthrough happened in the fourth session that April attended.

“The kids were asked to participate in a scavenger hunt at the hospital,” said Merrill. “They had a bingo chart of all the things they needed to collect, and I wasn’t sure if she’d be able to say one single word. But then she surprised me by asking a staff member in her quiet little voice, ‘do you have a sticker?’ Throughout the rest of the activity, she continued asking questions to different staff members which was so amazing to me.”

By the end of the 8-week program, April went from speaking in one word answers to talking in full sentences.

Merrill saw her daughter continue to progress in many ways – April began speaking to her grandmother, then in front of her kindergarten class.

“We were fortunate to have a kindergarten teacher who had awareness of the disorder and a supportive school faculty who has worked with us and April along the way,” said Merrill. “Some families don’t get the support from the school system that our kids need.”

However, there is still a long road ahead for April.

“Some days are better than others,” said Merrill. “She still freezes and can’t seem to speak. I can tell because moments before we walk into room, she’s animated and excited, but as soon as someone enters the conversation or she’s expected to have a conversation, her face turns blank.”

Still, Merrill says she has the tools she needs to help April break through and find her voice.

“With evidence-based intervention, selective mutism and other anxiety disorders are not lifetime disorders,” said Read. “They are treatable and kids can succeed in overcoming it. However, it is important for kids with selective mutism to seek intervention in order to address these symptoms.”

“Families of youth with selective mutism are often discouraged from seeking intervention because they hear that their child will ‘grow out of it,’ adds Read. “It’s a problematic myth that is not supported by clinical knowledge or research.”

There are now a growing number of researchers and clinicians collaborating within the field to study the disorder to develop further evidence-based treatments to help kids like April manage the challenges she may face in the future.

“We’re seeing a growing body of research around the disorder which has led to more awareness and early intervention for families who have children with selective mutism,” said Read. “We know that there are limited resources for treatment, and so we recognize the importance of providing services like our Selective Mutism Group to create a community of families that are able support one another.”

Merrill is hopeful that April will continue to make progress, especially with the support of the community that she has helped to build with parents that she met through the Selective Mutism Group.

“I’m so grateful to have had the opportunity meet other parents and learn from each other’s experiences,” said Merrill. “I created a Facebook page, Seattle, WA – Parents of Children with Selective Mutism, which allows parents whose children have selective mutism to become a vocal community that shares resources and provides support and awareness around the disorder.”

With each achievement April makes – whether it’s talking to a clerk at the grocery store or chatting with friends at school – the layers that conceal her vibrant personality slowly begin to shed.

“Recently, for the very first time, she sang and performed in front of people alongside kids in her school music class,” said Merrill. “I was so proud of April. I don’t think she would’ve made the progress that she did without the program. It’s made a huge impact for our family and I can’t be more thankful.”

Resources:

- Seattle Children’s Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine

- Selective Mutism Group

- Mood and Anxiety Program