The Pac-12 Football Championship Game featuring the Oregon Ducks and the Arizona Wildcats was more than just a football game to 18-year-old Sarah Roundtree, a freshman at the University of Oregon. It was the chance of a lifetime: a shot to win a $100,000 scholarship. The only catch to winning, she had to compete against […]

When Gailon Wixson Pursley came to Seattle Children’s, she was in so much pain she couldn’t walk. At 19 years old, Gailon was diagnosed with sarcoma, an aggressive cancerous tumor in her hip flexor muscle. Gailon’s treatment plan included surgery to remove the large tumor, radiation and chemotherapy, along with a long list of medications […]

As we head into the New Year, we’d like to reflect on some of the incredible clinical advancements of 2014 that show how our doctors have gone the extra mile for our patients. In the Children’s HealthLink Special video above, watch how futuristic medicine has saved the lives of the littlest patients at Seattle Children’s. From 3D-printed heart models to liquid ventilation, doctors […]

In honor of the New Year, we’re taking a look back at some of our most popular and memorable blog posts from 2014. Below is a list of our top 10 posts. Here’s to another great year of health news to come. Happy New Year! Lung Liquid Similar to One Used in Movie “The Abyss” […]

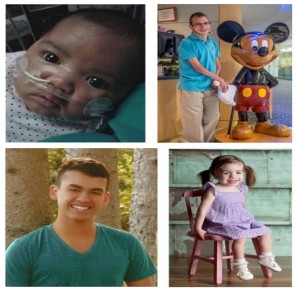

Sutton Piper, 3, was born with a metabolic disorder that made his muscles too weak for crawling, walking and talking. After being referred to Dr. Sihoun Hahn, a biochemical geneticist at Seattle Children’s, Sutton is bouncing on his mini-trampoline and chatting up a storm. Sutton Piper came into the world on his own terms: nine […]

Elise Pele had been in labor for hours awaiting the arrival of her baby girl, Tatiana, on the evening of Aug. 29. Elise remembers wanting desperately to hear her baby cry – a sign that everything was ok. But that cry never came. She saw Tatiana for only a few seconds before nurses rushed her […]

Researchers at Seattle Children’s are constantly asking questions and investigating new treatments with the goal of improving care for our patients. Two investigators from Seattle Children’s Research Institute recently came together to determine the best therapy for children suffering from infantile hemangiomas. A breakthrough treatment Right after Lorene Locke gave birth to her daughter Shakira, […]

In 2014, Andy and Maggie Oberhofer, of Portland, Ore., faced the most difficult dilemma of their lives. Their baby daughter, Greta, was dying. She had been diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia when she was just three months old and standard treatments were not working. Her family prepared for the worst. “Greta had barely survived chemotherapy […]

You may remember Kat Tiscornia from September of last year when she shared her experience of battling Ewing sarcoma and becoming “Titanium Girl.” Kat, now a sophomore at Mercer Island High School, asked On the Pulse if she could share an important message with those who cared for her at Seattle Children’s. We think you’ll enjoy […]

Dr. Katie Williams, a pediatrician and urgent care specialist at Seattle Children’s Bellevue Clinic and Surgery Center, lived every parent’s worst nightmare when her 1-month-old son turned gravely ill one Saturday evening in January. Here, Williams shares how her infant escaped the grip of death — and how she gained a new level of gratitude […]