Neurosurgeon Dr. Richard G. Ellenbogen and his former patient Nina Jubran share two important skills: As a surgeon and an artist, they both have great attention to detail and hands that are used to doing very delicate work. They also have another profound connection: Ellenbogen saved Nina’s life 12 years ago today when she came […]

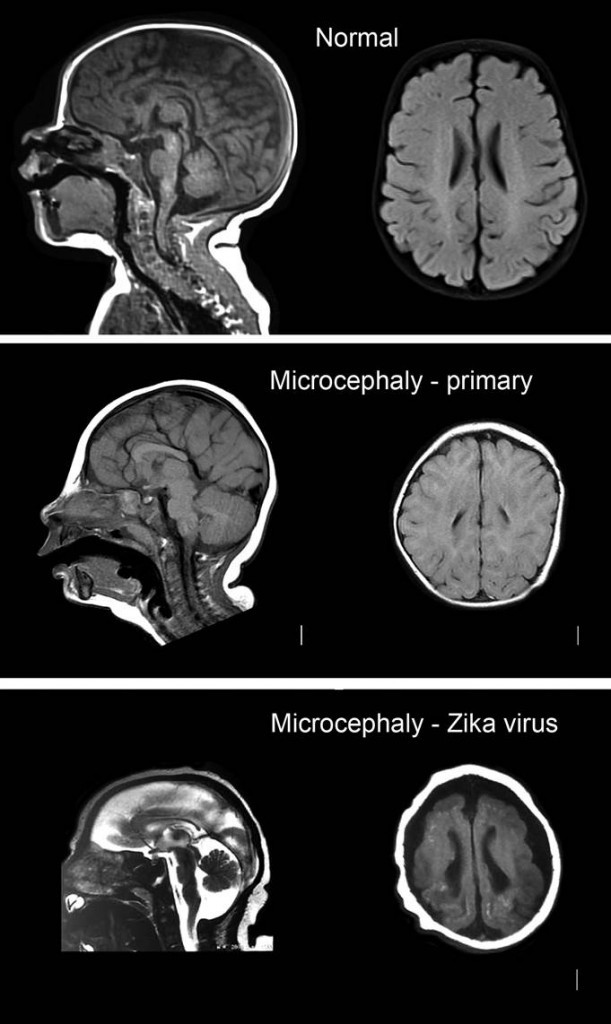

New research out today in the journal Cell Stem Cell indicates a likely link between the Zika virus and abnormal brain development. Scientists are studying if the spread of Zika by mosquitoes in Latin America is linked to the increased rates of microcephaly, a condition in which babies are born with unusually small heads. The study […]

The World Health Organization has declared the Zika virus and its potential link to birth defects a global health emergency. Scientists are studying if the spread of Zika in Latin America is linked to the increased rates of microcephaly, a condition in which babies are born with unusually small heads. Zika virus is transmitted mainly through the […]

What happens in our brains and bodies when we feel gratitude? We get a fuzzy feeling when we give thanks or receive it because we did something nice. But why does gratitude feel good? And how can families teach kids to express this sentiment? Dr. Susan Ferguson, a neuroscientist at the Center for Integrative Brain […]

Neurosurgeons at Seattle Children’s Hospital have long suspected that epilepsy patients who have surgery earlier in life have better outcomes than those that wait. Now they have data to confirm their instincts. In a study recently published in the Journal of Neurosurgery Pediatrics, lead author Dr. Hillary Shurtleff, neuropsychologist and investigator at Seattle Children’s Research […]

Imagine living every day of your life waiting for your child to have their next seizure. This is often the reality for parents of children with intractable epilepsy – a chronic form of epilepsy that can’t be controlled by medications alone. Every moment is plagued by uncertainty, and the world quickly becomes a place filled […]

For Dr. Jeff Ojemann, chief of the Neurosurgery Division and director of epilepsy surgery at Seattle Children’s, neuroscience is not just a passion – it’s the family business. His father, Dr. George Ojemann, was also a neurosurgeon and a national pioneer in the treatment of epilepsy. As we near Father’s Day, we asked Ojemann about his dad […]

Being the mother of a pediatric stroke survivor, I am thrilled that this month marks Pediatric Stroke Awareness Month in Washington state. As a nation, we have supported efforts of increasing awareness of stroke in general, however, pediatric stroke has received little awareness or research to date. Here we share our story in hopes of […]

Sage Taylor was born with a severe malformation in the right hemisphere of her brain – a condition that caused her to have hundreds of tiny “micro” seizures every day. Here, mom Sam Rosen reflects on their leap of faith with a neurosurgeon at Seattle Children’s and how Sage’s life took a dramatic turn for […]

The day doctors told Karen Twede her son Erik had Duchenne muscular dystrophy, she went straight home and searched for the mysterious illness in her medical dictionary. She read: “A progressive muscle disease in which there is gradual weakening and wasting of the muscles. There is no cure.” “My breath caught in my throat,” Twede […]